Some years back, director Francis Ford Coppola released The Godfather Trilogy 1901-1980: a chronologically reassembled

edit of all three of his Godfather

films. As appealing as it was (in a passive, brain-dead, sort of way) to have

the sprawling Corleone saga laid out in a fashion so as to make it impossible for even the

most distracted viewer to lose the narrative thread, the sad result was that in

the attainment of unequivocal comprehension, all poetry was lost. Robbed of the

sometimes poignant juxtapositioning of past and present events, The Godfather became just another

gangster film.

The artful manipulation of time in The Godfather films—the past coexisting with the present—is more than just a stylistic conceit; it's an essential representation of the films' narrative themes of destiny and predetermination. In Petulia, the conveyance of time as a nonlinear phenomenon reflective of the characters' fractured lives (a point of annoyance for several critics back in 1968), is no less fundamental to the telling of this distinctly Sixties, yet timeless, story.

Richard Lester’s Petulia is the story of a small group of very pretty people whose perfect-looking lives are nevertheless bloody battlefields strewn with the carnage of emotional (sometimes physical) violence every bit as senseless and arbitrary as the glaring images of the Vietnam War that flicker from the largely ignored TV sets running nonstop in every room. Depicted in an artfully disjointed style which intercuts flash-forwards and flashbacks with scenes occurring in the here and now, Petulia examines the tentative love affair between impulsive, unhappily married newlywed Petulia (Christie) and the generationally displaced surgeon Archie (Scott). Archie is an old-fashionedly decent man facing a kind of existential mid-life crisis in the midst of "The Pepsi Generation," and he doesn't know quite what to make of it all.

I saw Petulia for

the first time just two months ago, and given my predilection for all things Julie

Christie, it struck me as more than a little puzzling how this near-perfect little gem had managed to elude me all

these years. I suspected I would like it, but I didn't really expect to love it as much as I did. Funny, touching, and full of startling performances...it's so perfectly attuned to my tastes and interests it practically has my name on it. Advertised

at the time of its release as “The uncommon movie,” Petulia might well have added "unexpected” to the mix, for I've really never seen anything quite like it. Not only does it have Julie Christie at her most jaw-droppingly

gorgeous (EVER…and that’s saying something), but she, George C. Scott, and Richard Chamberlain bring an empathetic intensity to characters one might best describe as guardedly dispassionate.

Petulia is Richard Lester's savage

picture postcard satire of American life in the late Sixties. A time when

sentimentality was considered square, relationships tangential, and the

polished-metal, automated world of “now” was moving and changing so fast it stood in constant danger of leaving itself behind. As a dissection of an emerging cultural scene and its people, Petulia is a surprisingly focused social skewering considering its relative lack of distance (it's one of the few mainstream films commenting on the decade to actually have been filmed where and when what we commonly associate with '60s culture originated). Richard Lester (A

Hard Day’s Night, The Ritz) takes

a fragmented, psychedelic view of the gleaming-surfaced existence of jaded, wealthy

hippies and disillusioned, drop-out professionals. A world where the disenfranchised poor and people of color are

always glimpsed (just barely) on the periphery, and the hippies are just as phony and callous as the straights. The darkly

comic, fumbling interplay of these lost-and-found souls striving—often in shell-shocked

bemusement—to reach out to one another in a disposable, mechanized, instant

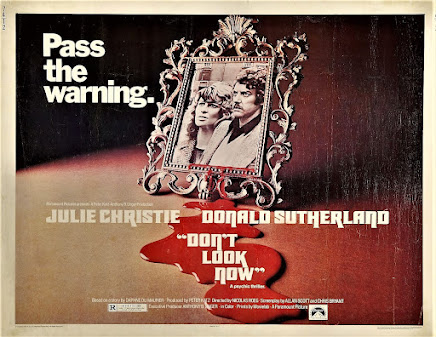

gratification society is rendered in strobe-light glimpses boldly captured by Nicolas Roeg’s (The Man Who Fell To Earth, Don’t Look Now) kaleidoscopic camera lens.

PERFORMANCES

No one does sham superficiality better than Julie Christie. From Darling's narcissistic Diana Scott, Far From the Madding Crowd's perniciously thoughtless Bathsheba, to the emotionally vacant Linda Montag of Fahrenheit 451, Christie has made a career of adding depth and dimension to otherwise unsympathetically shallow characters.

The walking contradiction that is Petulia Danner: arch posturing one moment, self-recriminating anguish the next, is one of Julie Christie's strongest most persuasive performances.

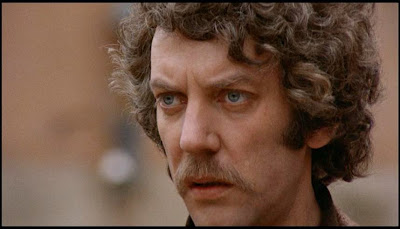

I can't say I've ever cared much for George C. Scott (who somehow grows increasingly more handsome as the film progresses) but I think he is rather spectacular here. He avoids the usual self-pity that comes with these kinds of roles and makes Archie into a strong, very likable character you come to care a great deal about. It's a most effective dramatic device when a staunchly unexcitable character in a movie breaks into a smile, and when this happens in Petulia, it just about breaks my heart.

Special mention must also be made of Richard Chamberlain (then known exclusively for TV's Dr. Kildare and as a heartthrob romantic lead) daringly cast against type and delivering an overwhelmingly chilling portrayal of a man who is a physically perfect, psychologically damaged, Ken doll.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

A film set in '60s San Francisco is bound to be visually vivid, and Petulia is a marvelous-looking movie whose color photography is as expressive as it is overwhelming. There are psychedelic light shows accompanying musical appearances by The Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin, striking vistas of Bay Area locations, and the candy-colored mod fashions of the day take on a fairly 3D effect.

My partner was the first to take note of the beige/brown cheerlessness of Archie's bachelor apartment (top) contrasting so expressively with Petulia's fraudulently festive pink and yellow boudoir (below).

On the strength of one month's ownership of the DVD and three viewings, Petulia has become my absolute favorite Richard Lester film. The first American feature from a director known for his bold comedic style, Petulia is not as great a thematic departure as it at first appears. There are plentiful examples of Lester's penchant for absurdist humor, caustic irony, and the sad/funny details of human interaction. But what distinguishes Petulia for me is the humanity at the core of this little microscopic vision of the world. That and the sophisticated style of its execution. In that, Petulia is indeed an uncommon movie.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

The artful manipulation of time in The Godfather films—the past coexisting with the present—is more than just a stylistic conceit; it's an essential representation of the films' narrative themes of destiny and predetermination. In Petulia, the conveyance of time as a nonlinear phenomenon reflective of the characters' fractured lives (a point of annoyance for several critics back in 1968), is no less fundamental to the telling of this distinctly Sixties, yet timeless, story.

|

| Down on Me Well-heeled attendees of a charity fundraising dance "Shake for Highway Safety" react to the rock group Big Brother & the Holding Company (Janis Joplin) |

Richard Lester’s Petulia is the story of a small group of very pretty people whose perfect-looking lives are nevertheless bloody battlefields strewn with the carnage of emotional (sometimes physical) violence every bit as senseless and arbitrary as the glaring images of the Vietnam War that flicker from the largely ignored TV sets running nonstop in every room. Depicted in an artfully disjointed style which intercuts flash-forwards and flashbacks with scenes occurring in the here and now, Petulia examines the tentative love affair between impulsive, unhappily married newlywed Petulia (Christie) and the generationally displaced surgeon Archie (Scott). Archie is an old-fashionedly decent man facing a kind of existential mid-life crisis in the midst of "The Pepsi Generation," and he doesn't know quite what to make of it all.

Just as Coppola's use of flashbacks in The Godfather created a sense of history encroaching upon the present, Petulia is an almost-love-story

told in a time-tripping, hopscotch fashion so organic to the era (the swinging Sixties); the place (Summer of Love San Francisco); and characters (the beautiful

people), that it’s impossible to imagine the film realized in any other way.

|

| Julie Christie as Petulia Danner |

|

| George C. Scott as Archie Bollen |

|

| Richard Chamberlain as David Danner |

|

| Shirley Knight as Polo (Prudence) Bollen |

|

| Joseph Cotten as Mr. Danner |

|

| Although they share no scenes together, Petulia reunites Kathleen Widdoes (pictured) with her The Group co-star, Shirley Knight |

Petulia (based on

the John Haase novel, Me and the Arch

Kook Petulia) is very effective, not to mention outrageously stylish, in the ways it depicts

the messy complexity of relationships. Contrary to what songs, romance novels,

and fairy tales would have us believe, really connecting with another human

being is a frustratingly difficult business. It's imperfect, inconsistent, and

comprised of a million little disappointments and uncertainties, all tethered

to an overpowering but seldom acknowledged need for human contact.

The straightforward Archie can’t make head-nor-tails of the

captivating but confounding Petulia, who is herself of two minds about her

beautiful but abusive husband, David. Polo, Archie’s ex-wife, is not quite over

him, yet seems to have leapt into a compromise relationship. Meanwhile, their friends Barney and Wilma (?!) -Arthur Hill and Kathleen Widdoes - whose own marriage is

falling apart, scheme to have them reconcile. These emotionally inarticulate couplings

form a roundelay of missed chances and miscommunications endlessly reenacted by

the uniformly dissatisfied protagonists. Individuals whose words and actions seem

to be forever at cross purposes with their desires.

As Petulia is as

much a social satire as a poignantly bleak meditation on emotional authenticity

(“Real, honest-to-God tears, Petulia?”),

the picture of America that Lester paints is one of alienating mechanization and deceptive appearances. Richard Lester’s San Francisco is one of automatized

motels; switch-on fireplaces; indoor flowers that die when exposed to real

sunlight; decoy hospital room TV sets; sullen flower children; nuns driving Porches; topless restaurants;

gloomy all-night supermarkets; and kiddie excursions to Alcatraz Prison (which

is a reality now, but was not, if I remember correctly, the case back in 1967).

|

| Among the row houses of Daly City, Archie seeks the assistance of two two non-cooperative hippies (that's WKRP's Howard Hessman in the pink shirt) |

No one does sham superficiality better than Julie Christie. From Darling's narcissistic Diana Scott, Far From the Madding Crowd's perniciously thoughtless Bathsheba, to the emotionally vacant Linda Montag of Fahrenheit 451, Christie has made a career of adding depth and dimension to otherwise unsympathetically shallow characters.

The walking contradiction that is Petulia Danner: arch posturing one moment, self-recriminating anguish the next, is one of Julie Christie's strongest most persuasive performances.

I can't say I've ever cared much for George C. Scott (who somehow grows increasingly more handsome as the film progresses) but I think he is rather spectacular here. He avoids the usual self-pity that comes with these kinds of roles and makes Archie into a strong, very likable character you come to care a great deal about. It's a most effective dramatic device when a staunchly unexcitable character in a movie breaks into a smile, and when this happens in Petulia, it just about breaks my heart.

Special mention must also be made of Richard Chamberlain (then known exclusively for TV's Dr. Kildare and as a heartthrob romantic lead) daringly cast against type and delivering an overwhelmingly chilling portrayal of a man who is a physically perfect, psychologically damaged, Ken doll.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

A film set in '60s San Francisco is bound to be visually vivid, and Petulia is a marvelous-looking movie whose color photography is as expressive as it is overwhelming. There are psychedelic light shows accompanying musical appearances by The Grateful Dead and Janis Joplin, striking vistas of Bay Area locations, and the candy-colored mod fashions of the day take on a fairly 3D effect.

My partner was the first to take note of the beige/brown cheerlessness of Archie's bachelor apartment (top) contrasting so expressively with Petulia's fraudulently festive pink and yellow boudoir (below).

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

It's always struck me as a curious phenomenon how so many films from the '80s and '90s can appear so dated to me, yet most of my favorite films from the late -'60s and '70s seem to have a timelessness about them. I don't pretend to know the reason, but I suspect it's because so many '60s and '70s films are about people and relationships, while '80s and '90s films are chiefly the result of pitches, formulas, and focus groups. Ignore the swinging '60s window dressing (but who would want to?) and Petulia is as topically relevant today as it was in 1968. Perhaps more so

|

| Estrangement. The natural consequence of erecting barriers in the avoidance of pain |

On the strength of one month's ownership of the DVD and three viewings, Petulia has become my absolute favorite Richard Lester film. The first American feature from a director known for his bold comedic style, Petulia is not as great a thematic departure as it at first appears. There are plentiful examples of Lester's penchant for absurdist humor, caustic irony, and the sad/funny details of human interaction. But what distinguishes Petulia for me is the humanity at the core of this little microscopic vision of the world. That and the sophisticated style of its execution. In that, Petulia is indeed an uncommon movie.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012