From Alfred Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943):

Joseph Cotten- "How was church, Charlie? Did you count the house? Turn anybody away?"

Teresa Wright- "No, room enough for everyone."

Cotten- "Well, I'm glad to hear that. The show's been running such a long time I thought maybe attendance might be falling off."

When it comes to movies based on the final days in the life of Jesus of Nazareth, Hollywood has been running a near-nonstop show on the subject since 52-year-old H.B. Warner portrayed the screen's first grandfatherly Jesus in Cecil B. DeMille's 1927 silent classic, King of Kings. Since then, the movie industry has cranked out a new Jesus film every couple of years or so. Sometimes just to make use of new technological advancements (sound, color, Cinemascope), other times, merely to keep in step with the times, theologically speaking.

Thus, with so many iterations of the same tale already committed to celluloid, it's fair to assume that by 1973, when the 1971 Broadway rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar was ultimately adapted for the screen, no one involved harbored any illusions that audiences would be flocking to the film eager to find out how it all comes out.

The major selling point of Jesus Christ Superstar was not the story, per se, but its telling. This was to be the screen's first all-singing, all-dancing Jesus, and its daring, once-controversial, "hook" was to have the Passion Play told (with a decidedly youthful slant) from the perspective of, and in sympathy with, the apostle Judas. In Jesus Christ Superstar Judas sees Jesus not as a God, but merely a mortal man guilty of believing his own publicity. What distinguishes the film version is that it is not as decided on the fact of Jesus' mortality as the stage production, and that uncertainly has been presented in such a manner as to provoke questions more than provide answers.

|

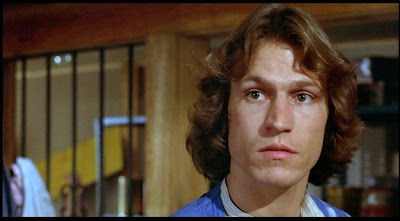

| Ted Neeley as Jesus |

|

| Carl Anderson as Judas |

|

| Yvonne Elliman as Mary |

|

| Barry Dennen as Pontius Pilate |

|

| Contemporary symbols of military power provoke and bedevil the morally besieged Judas |

|

| Armed with machine guns and spears, Roman guards march in tank tops and battle fatigues. |

|

| The angel Judas descends from heaven by way of an industrial crane. |

America's hippie-inspired Jesus movement of the late 60s (Jesus was, after all, the first long-haired, counter-culture revolutionary) which fueled pop-culture works like Jesus Christ Superstar and its off-Broadway cousin, Godspell (1971), greatly influenced my perception of religion during my teen years.

|

| June 1971 |

Between the years 1971 and 1974, I attended Saint Mary's College High School

Add to this the fact that virtually every citizen of Berkeley at the time seemed to look exactly like the flower-children cast of Jesus Christ Superstar (Saint Mary's custodian/caretaker was a ringer for Ted Neeley's Jesus Christ, only taller, muscular, and with really tight jeans—can't tell you all the spiritual inner-conflict that little teenage crush inspired) and you get a good idea of why looking at Jesus Christ Superstar today feels for me a bit like watching a home movie.

Add to this the fact that virtually every citizen of Berkeley at the time seemed to look exactly like the flower-children cast of Jesus Christ Superstar (Saint Mary's custodian/caretaker was a ringer for Ted Neeley's Jesus Christ, only taller, muscular, and with really tight jeans—can't tell you all the spiritual inner-conflict that little teenage crush inspired) and you get a good idea of why looking at Jesus Christ Superstar today feels for me a bit like watching a home movie.

|

| The troupe arriving by bus to enact the Passion Play in the desert brings to mind all those Catholic School weekend retreats where we kids were encouraged to "rap" and "tell it like it is" |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

In spite of my Catholic upbringing, I confess that I find it difficult sometimes to become emotionally moved by religious films. I can enjoy the spectacle, the performances, and the moral of the narrative; but few things are more disconcerting and distancing than having ethics-challenged Hollywood try to convince me of the value of a virtuous life, simply led. Thus, one of the great pleasures of Jesus Christ Superstar is its ability to be enjoyed from either a secular or spiritual perspective. Jewison achieves something rather extraordinary in having devised a timeless, utterly cinematic approach to the material (the past and present keep bleeding into one another) that doesn't merely "open up" the play, but rethinks and re-imagines it in a profoundly fundamental way.

|

| The Last Supper - hippie style |

The hippy-dippy / flower child look of the film, which so many revivals of the show are so quick to discard, is ideally suited to the time-mashup approach of Jewison's vision. It strikes me as ingenious that we are invited to make parallels between Jesus and his followers and the youth of the '70s. It's a concept that gives the events a timeless appeal while encouraging us to take subliminal stock of the way the hairstyles and modes of dress of '70s-era hippies and college students harken back to the look of ancient Israel.

In stressing the contemporarily familiar, Jesus Christ Superstar establishes a narrative point of view that asks us to question the difference between the myth and the man. And it does so in a way that manages to be both impassioned and reverent, yet refreshingly free of the kind of fervent self-seriousness that mars many films about religion. The non-traditional score (orchestrated pop/rock) and refreshingly ambiguous nature of its visuals (what time is all of this taking place in?) invite the re-examination of over-familiar events and characters.

PERFORMANCES

In stressing the contemporarily familiar, Jesus Christ Superstar establishes a narrative point of view that asks us to question the difference between the myth and the man. And it does so in a way that manages to be both impassioned and reverent, yet refreshingly free of the kind of fervent self-seriousness that mars many films about religion. The non-traditional score (orchestrated pop/rock) and refreshingly ambiguous nature of its visuals (what time is all of this taking place in?) invite the re-examination of over-familiar events and characters.

PERFORMANCES

In listening to three decades' worth of covers, revivals, and re-recordings, I still find this version of Jesus Christ Superstar to be the best sung of the lot. This has a lot to do with the era in which I grew up and the pop sound I'm accustomed to, but the arrangements, orchestrations, and vocal performances here are just top-notch. This is especially true of the late Carl Anderson, whose powerfully clear and expressive voice can still give me goosebumps. Every singer in this role has had to live up to Anderson

Oh, and as every rule has its exception: when I wrote earlier that I'm not easily moved by religious films, that still stands; with the exception of Ted Neeley's performance of the song "Gethsemane (I Only Want to Say)." It's the only part of the film that can consistently bring tears to my eyes. Dramatically shot and emotionally intense, it is a really beautiful bit of filmmaking aided immensely by Neeley's wrenching vocal performance. It's the dramatic centerpiece of the film.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Where Jesus Christ Superstar truly shines is in the stark freshness of its visuals. It's a stunning-looking film from every angle. At turns, whimsical, epic, theatrical, and poetic, it is one of those rare adaptations of a stage success that achieve multiple moments of pure cinema.

When I first saw the film, glitter, disco, and Elton John glitz was all the rage, so I was a bit disappointed that Jesus Christ Superstar didn't look more like the stage production, As the years have gone by, I'm glad the film didn't mire itself in a look that would have given it the feel of a '70s variety show. Sure, the hippie style employed may be labeled "dated," but for me, it's a look evocative of the time which created this show's perspective (the '60s) - and somehow that feels more than perfect...it's ideal.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

The dancing in Jesus Christ Superstar is phenomenal. And all those thin, lithe, 70s bodies are a welcome change from the earthbound, often clumsy-looking, gym-puffed bodies of so many dancers today.

My absolute favorite number in the film is "Simon Zealotes." It hits me from the opposite end of the emotional spectrum of Neeley's "Gethsemane" soliloquy. It's joy and energy personified, given vivacious, eye-popping life by some of the most fantastic dancers doing dazzling choreography ever filmed. It has the power to bring me to a state of childlike elation in a single viewing. Even now, all I can think when I look at it is, WOW!!! Now that is what I call dancing! (Watching it makes me feel proud to be a dancer, although, if I were to try any of these moves now, I'd likely break into a million pieces like Meryl Streep and Goldie Hawn in Death Becomes Her.)

Jesus Christ Superstar is yet another one of those motion pictures that grows better with age. Its themes nostalgically remind me of my youth, yet its enduring innovativeness as a film makes me appreciate Norman Jewison's commitment to making this particular "long-running show" one that will hold timeless appeal for new generations.  |

| Judas Kiss |