Back in 1977 I recall asking a friend if she was as eager as

I to see the new Donald Cammell film Demon

Seed opening at theaters that week. Her reply: "Ugh! Hollywood

Her response surprised me, but it really shouldn't have. Not if I'd given even two seconds' worth of thought to how the film's premise might sound from her perspective.

My friend and I were classmates at

film school, drawn together by a love of offbeat movies and a shared fondness for Cammell's remarkable

directing debut, Performance (1970). Given that Demon Seed was only Cammell's second film in

six years, I thought my friend would find provocative the prospect of a director

as artistically idiosyncratic as Cammell taking on a genre film. Indeed, in summary, the plot read like something better suited to William Castle or Roger Corman: a supercomputer imprisons a woman (Julie Christie) in her

home, intent on impregnating her and creating a new life form.

I mean, how could my friend so oversimplify what was

obviously sure to be some kind of meta-commentary on the uneasy relationship

between man and machine. An ages-old conflict contrasting the life-affirming intellectual and emotional attributes of the contemporary woman vs. the cold, patriarchal dominance of

technology? It was like someone saying Rosemary's Baby was just about a hell-beast raping a mortal woman. Certainly, my friend could see there HAD to be so much more to Demon

Seed than the exploitative theme and the offensive premise.

And what about the Julie Christie connection? Surely Julie

Christie—that skilled, intelligent, serious-minded movie icon of the '60s, who

publicly eschewed Hollywood stardom and cheesecake glamour for serious roles. Who

turned her back on untold millions due to her level-headed, principled, proto-feminist

disinterest in portraying helpless girlfriends and supportive male appendages. Surely SHE wouldn't participate in a film that degrades women! Would she?

|

| Julie Christie as Dr. Susan Harris |

|

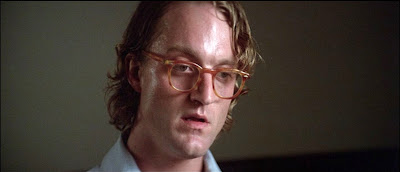

| Fritz Weaver as Dr. Alex Harris |

|

| Gerrit Graham as Walter |

|

| Robert Vaugh as the voice of Proteus IV |

Well, here it is some 34 years and countless viewings later,

and as far as I'm concerned the jury is still out on whether my friend's

diminution of Demon Seed was a rash oversimplification or if she simply hit the nail on the head.

The marriage of child psychologist Susan Harris

(Christie) and computer scientist Alex Harris (Weaver) becomes strained following

the loss of their child to leukemia. Susan fears Alex has grown increasingly

remote and unemotional, immersing himself in work she views as dehumanizing technology. Specifically, the creation of an organic super-computer named

Proteus IV. Attempting a trial separation, Susan opts to remain alone in their

spacious, fully-automated, fortress-secure home, run by an all-seeing computer named

Alfred (a.k.a., Red Flag #1).

It's clear Alex is confronting his grief in the only way he

knows how, by channeling his energies into Proteus IV discovering a cure for

the kind of cancer that took the life of their child. And indeed, it is Alex's emotional involvement that prevents him from seeing that his colleagues and subsidizers are more interested in the financial and political potential of Proteus

IV.

But Proteus is an artificial intelligence with a moral code (warped as it is), a voice (Robert Vaughn), and a peculiarly masculine tendency to insist he's always right. Even in the face of blatant contradictions. When ordered to conduct

research into an undersea mining operation that would disrupt the ecosystem,

Proteus high-mindedly declares, "I refuse to assist you in the rape of the

earth!"

A point well-taken were it not for the hypocritically nasty bit of business

he/it feels perfectly vindicated in embarking upon just moments later; the raping

and impregnation of Susan. What's the purpose of this violent act? So that he/it, Proteus IV, who seems to possess all the ignorance as well as the intelligence of mankind, can feel the sun on its face and achieve the kind of immortality that only an offspring can guarantee. Or something

like that.

You see, the objective of Proteus' plan to procreate

fluctuates from altruistic to despotic, depending upon whom he's speaking to and what it is he/it is trying to reason/intimidate them into doing.

And therein lies the paradox of Proteus IV. Perhaps intentionally, due to Proteus' inconsistent shifts from sadistic tormentor to world savior, we are never sure if we are meant to side with Proteus' rather logical, humane arguments (the Icon Industries money men are portrayed as villainous fat cats), or if Proteus IV is just a

machine gone mad. Perfectly valid to have that point left ambiguous, but as the film is constructed, it feels less like food for thought and more like a lack of focus and sloppy storytelling. It certainly doesn't help that when it wishes to persuade, Proteus speaks in the soothing, calming tones of a meditation guru and shows trippy psychedelic lights. Yet when it wants to get its way, employs the emotional abuse tactics and psychological gaslighting games of an abusive husband ("Why do you make me do these things?").

|

| The cerebral Alex is frequently photographed in cold, windowless surroundings. The nurturing Susan is seen amidst sunshine and vegetation. |

Demon Seed holds out hope because of the intelligence of Julie Christie's performance and the validity of the horror film/sci-fi thriller conflict as initially presented. But as much as I think of this as one of Christie's best performances, I can't shake the feeling that Donald Cammell's opaque direction is not as focused as a piece like this requires. It's weird to watch a movie like this, one that sparks so many internal debates about its themes, while wondering if the guy behind it all is even aware of its subtexts.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

I'm not unduly fond of science fiction, but I do enjoy a

good psychological thriller. Demon Seed

does a lot of things wrong, but what it does particularly well is create a

palpable sense of dread and tension from a situation that is the stuff of nightmares. Julie Christie's ability to convincingly take her character all the way from mild annoyance, defiance, rage, bewilderment, to abject terror is a thing to behold. It's largely Christie emoting in empty rooms, but in these melodramatic circumstances, her performance is so unforced and natural that we buy into the plot's absurdities.

Indeed, the absolute smartest thing the makers of Demon Seed did was to hire Julie

Christie. Without question she is the single reason the film works at all, her assured

performance never once succumbing to the usual "helpless victim" clichés

of the genre. It's a major asset that Christie is an actress of sensitivity capable of conveying a vulnerability that is at the same time very strong. The film is saved from being a tedious exercise in sadism by the fact that Christie comes across as a woman without a weak bone in her body. I can't think of another actress more believable as a match for, and worthy adversary of, a diabolical super-brain.

As Mia Farrow's performance transcended the horror genre and elevated Rosemary's Baby to the level of a modern classic, Julie Christie achieves as much here, but the film surrounding her standout performance isn't up to the task. If anything, she's so good that she only calls attention to how weak the script is and how poorly she's served by it.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

There's no denying that Demon

Seed has an intriguing premise that thought-provokingly meshes the

techno-paranoia of 2001: A Space Odyssey

with the body-invasion terror of Rosemary's Baby. But unlike either of those films,

Demon Seed suffers from the feeling that it is perhaps a couple of story

conferences short of fully understanding what it wants to say about it all.

Ira Levin & Roman Polanski mitigated a lot of potential

criticism concerning Rosemary's Baby

(misogyny, sensationalism, violence against women as entertainment) through the

firm establishment of a consistent point of view: Rosemary's. It also had a defined moral perspective in having Rosemary's lapsed Catholicism serving to reflect the morally ambiguous tone

of the events of the plot (i.e., at the conclusion, it's suggested that her love for her child may supersede her rejection of the immorality of evil). Most of all Rosemary's Baby expressed awareness and understanding of the story's larger social implications. The film's graphic depiction of the patriarchal dominance that religion and society have over women is countered by the very sympathetic attitude it has towards Rosemary.

Demon Seed at times feels like the director sympathizes with Proteus IV.

Like Rosemary's Baby,

Demon Seed has at its center, a

vulnerable, yet smart and resourceful woman. But instead of heightening audience

identification/empathy through the presentation of events from her perspective

(an easy enough thing to accomplish given that we've all felt helpless to the

whims of machines at one time or another),

Demon Seed keeps us at a

remove and puts us in the distasteful position of sharing the voyeuristic eyes

of Proteus IV.

|

| Seeing through the distorted lens of Proteus IV |

In all the scenes with Susan engaged in a test-of-wills/battle-of-wits with Proteus IV, I kept hoping for the film to reconcile in some meaningful

way its initial scenes emphasizing Susan's belief in the importance of feelings

and expressing emotions. But the film ends without a viable justification, beyond genre

entertainment, for asking us to endure the many protracted scenes of physical

and psychological abuse perpetrated against Julie Christie for the bulk of the

film.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the mishandling of Demon Seed's final moments, which is

staged for maximum dramatic payoff, but does so at the cost of shifting focus

from Susan and placing the viewer in the shoes of the science-minded Alex (who

registers about three seconds of concern for his wife before becoming near

orgasmic at the thought of the scientific miracle in the basement). Yes, the

audience is clamoring to see the baby at this point too, but a more skilled

director might have taken precautions to prevent Susan from being shunted to

the sidelines at the end of the film in which she has heretofore been front and center.

It's a gross miscalculation of the importance of audience identification, and one of the main reasons why, in the end, I think that Demon Seed is just not up to the task set forth by its premise.

It's a gross miscalculation of the importance of audience identification, and one of the main reasons why, in the end, I think that Demon Seed is just not up to the task set forth by its premise.

It succeeds as a more-thoughtful-than-usual sci-fi thriller,

but trips itself up by failing to comprehend how uncomfortable (if not

downright unpleasant) audiences are likely to find a film that asks one to bear

witness to a woman's victimization all in service of an academic, techno-geek debate.

|

| The triumph of technology over emotion? Demon Seed ends on an ambiguous note, with Susan enigmatically studying her child/creation from the sidelines. No embraces, no tears, no tenderness |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011

.JPG)

.JPG)