Like counting the rings of a tree, there will likely come a

day when a person’s age can be calculated by the number of films released in

that individual’s lifetime that have fallen prey to the dreaded remake. Of course,

such calculations would be mathematically calibrated to allow for the increased

percentage numbers afforded genre films (Carrie,

The Shining, The Stepford Wives, Psycho, et.al,) obviously Hollywood’s favored

source for idea-harvesting.

Coma, one of my

favorite '70s thrillers, has recently been given the TV miniseries treatment.

And while I wish it luck (ever the bullheaded traditionalist, I didn’t watch it

and don’t plan to), seriously…can any remake ever hope to replicate in any dramatically

meaningful way, that transcendent feminist moment in American cinema when heroine

Geneviève Bujold doffed her wedged espadrilles and pantyhose before crawling

through the bowels of Boston Memorial Hospital in search of the cause of all

those suspicious coma cases? After years of women in thrillers and horror films

falling victim to their feminine finery (running in heels and twisting an ankle being the genre standard), this small act of practicality was such a revolutionary repudiation

of a sexist genre cliché that on the opening weekend screening of Coma I attended back in February of 1978, the audience I saw it with actually broke into

applause!

|

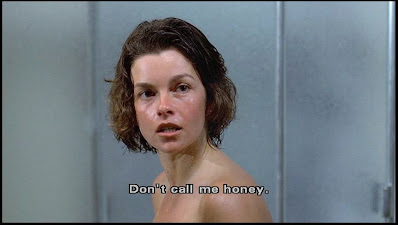

| Genevieve Bujold as Dr. Susan Wheeler |

|

| Michael Douglas as Dr. Mark Bellows |

|

| Richard Widmark as Dr. Harris - Chief of Surgery |

|

| Elizabeth Ashley as Mrs. Emerson |

|

| Rip Torn as Dr. George |

|

| Lois Chiles as Nancy Greenly |

|

| Tom Selleck as Sean Murphy |

|

| Ed Harris as Pathology Resident #2 (film debut!) |

The post-Watergate years may have been depressing as hell,

but all that resultant disillusionment and cynicism was a bonanza for the

suspense thriller genre. The pervading sense of skepticism and uncertainty that

was the cultural by-product of such a large-scale political betrayal fueled and found catharsis in a great many fascinating films of the '70s. We had thrillers about

conspiracy theories – The

Parallax View (1974); morally confused private eyes – Night Moves (1975); and personal privacy paranoia – The Conversation (1974). Coma remains

one of my personal favorites because it ratchets up the tension of the conspiracy

theory thriller by combining it with the combative feminist-era sexual

politics of The Stepford Wives.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

Rosemary’s Baby, The Stepford Wives, and Klute rank high on my list of

unforgettable thrillers because each is a genre film (horror film, suspense

thriller, crime mystery) that seizes upon an element of the cultural zeitgeist to create

something marvelously new and chilling out the rote and familiar. The medical thriller at the center of Coma is intriguing enough (are patients deliberately being put

into comas, and if so, why?), but the paranoia is amplified by having the usual

disbelieved protagonist be a woman doctor in a field where women number in the minority and their concerns dismissed by patronizing superiors.

The day-to-day condescension Geneviève Bujold’s Dr. Wheeler faces from her male co-workers takes on an increasingly ominous air when her growing anxiety and rational concern that something nefarious is afoot at Boston Memorial is met with “Don’t bother your pretty little head about it” disregard from her superiors. Especially the creepily paternal Chief of Surgery (Richard Widmark), who treats a serious professional discussion with Dr. Wheeler as if he's Andy Hardy's father, asked to give a heart-to-heart.

|

| The Men's Club Coma uses institutionalized sexism as fodder for a marvelously engrossing paranoid thriller |

The day-to-day condescension Geneviève Bujold’s Dr. Wheeler faces from her male co-workers takes on an increasingly ominous air when her growing anxiety and rational concern that something nefarious is afoot at Boston Memorial is met with “Don’t bother your pretty little head about it” disregard from her superiors. Especially the creepily paternal Chief of Surgery (Richard Widmark), who treats a serious professional discussion with Dr. Wheeler as if he's Andy Hardy's father, asked to give a heart-to-heart.

It’s

established early on in the scenes between Dr. Wheeler and her professionally

ambitious boyfriend, Dr. Mark Bellows (Douglas) that she is hypersensitive to the sexism and lack of respect she's expected to just accept as part of the price of working in semi-hostile, all-male environment of professional

medicine. The film makes a point of showing us scenes where the in-hospital workplace talk is full of men making casually demeaning

comments to or about women.

Much like in Rosemary's Baby when Rosemary’s pregnancy itself is diagnosed (by men) as being the source of her paranoia about her neighbors; Dr. Wheeler’s feminism and relationship troubles are viewed as being part of her perceived-as-hysterical suspicions about the male staff at her hospital. As her frustration mounts from not being able to convince anyone at the hospital that there is something to be concerned about, reactions from the male staff (she seems to be the only woman doctor there) range from flat out dismissals to bristling at the audacity of a woman daring to challenge the knowledge and authority of men. It's a wonderful add-on device that lends to Coma a subtext that fuels paranoia with extra layers of workplace frustration born of women not being taken seriously in male-dominated spaces.

PERFORMANCES

I had the grave misfortune of having my first-ever exposure

to Geneviève Bujold occur with the

movie Earthquake (1975); a film whose most terrifying image was that of

the lovely French-Canadian actress canoodling with the Skeletor-like countenance of

Charlton Heston. In the ensuing years, I’ve enjoyed her performances in several notable films (1988's Dead Ringers

is a must-see), but I guess I have a special place in my heart for Coma. As her first real starring solo venture, I thought it was to be the

film that launched her to stardom. As I’ve said in a previous post, Bujold

represented to me the direction I thought films were going to take in terms of motion

picture leading ladies in the '70s. She was quirky, radiated intelligence, and embodied a

non-traditional beauty coupled with remarkable acting skills. As the '80s fate of

Debra Winger attested, Hollywood still preferred their leading ladies vapid and

pliable, so the promise of Bujold was never realized (at least to my

satisfaction).

Still, Bujold is terrific here, spunky and sharp with that great throaty voice of hers and those darkly intelligent, inquisitive eyes. She adds so much dimension to her role that she keeps character and motivation at the forefront, preventing Coma from becoming mired in its medical thriller plot. Unlike the kind of actress usually cast in roles like this (I call your attention to Lesley-Anne Downs’ implausible Egyptologist in Sphinx, another film based on a Robin Cook novel) Bujold is actually believable as a physician and is not required to scream every 15 minutes.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

Unable to convince anyone of her suspicions, Dr. Wheeler's quest takes her to the architecturally foreboding Jefferson Institute. The scenes taking place at this futuristic chronic care facility (whose actual purpose I won't reveal here) are Coma's big set-pieces, and they really don't disappoint. A concrete and steel variation on the typical thriller haunted house, the Jefferson Institute scenes are notable not only for the poetic-nightmare images of roomfuls of bodies suspended in techno limbo, but also for the unforgettably bizarre performance of Elizabeth Ashley as Mrs. Emerson, the Institute's equivalent of a gargoyle at the gate.

By Coma's midpoint, when the film's well-established atmosphere of tension is just about sunk by an interminable "romantic weekend" montage, Ms. Ashley appears and reboots the film back into high gear. Her introductory scene with Bujold is a classic that I remember had the audience laughing in a way that brought them even more into the film. You want to know if she's a real person or a robot. As the unblinking and inscrutable head of the Institute, Ashley carves an indelible impression and is one of my favorite characters in the film.

|

| The Jefferson Institute Coma knows that in real life, a large, impersonal medical building like this is far more terrifying than any Gothic castle. |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

|

| "You'll be getting a bill from each of us in the mail." |

Remakes get a bad rap, but for every totally pointless rehash of a classic (Straw Dogs), there's a film like 1978's marvelous Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a retread that's really a re-imagining. I'm not sure what the remake of Coma will seize upon as a justification for its existence (the feminist subtext - which to my way of thinking is more relevant than ever - might be perceived as being dated), but unless it devotes itself to correcting some of this film's flaws (a few loose narrative threads, that mysterious hired killer), I think I'll stick to this imperfect but ever-so-satisfying relic from a time when even genre films felt that it was also important to comment on the world we live in.

AUTOGRAPH FILES

In 1982 I had the opportunity to see Elizabeth Ashley co-star on Broadway with Geraldine Page and Carrie Fisher in the play, Agnes of God. As one might imagine, the experience was electrifying. Although very faded, Ashley's signature is on the bottom of the Playbill above.

To read more about Coma:

Another informative and fun post on "Coma" at Poseidon's Underworld

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2008 - 2012AUTOGRAPH FILES

In 1982 I had the opportunity to see Elizabeth Ashley co-star on Broadway with Geraldine Page and Carrie Fisher in the play, Agnes of God. As one might imagine, the experience was electrifying. Although very faded, Ashley's signature is on the bottom of the Playbill above.

To read more about Coma:

Another informative and fun post on "Coma" at Poseidon's Underworld