The Waiting Is Over...The Love Machine is on the Screen!

So declared the graphically austere poster ads (a gold ankh against a simple black background) heralding the arrival of The Love Machine—sorry, Jacqueline Susann's The Love Machine—to

movie theaters in 1971. Hard to believe when looking at the film now, but there actually was a degree of anticipation attending

the release of The Love Machine, the big-screen adaptation of Susann's 1969 best-selling follow-up novel to the

phenomenally successful Valley of the Dolls.

Much of the anticipation was due to so much having transpired

in the four years since 20th Century Fox first released Valley of the Dolls to big boxoffice and a torrent of lousy reviews in

1967. First and most significantly, Jacqueline Susann had proven herself a viable boxoffice name in her own right, capable of selling tickets regardless of the project's relative artistic or critical merit. Secondly, movies themselves had grown increasingly permissive in terms of nudity and language since 1967

(Fox's own Myra Breckinridge had seen

to that); thus, there existed,

at least among Jacqueline Susann's broad fan base, the hope that the film of The Love Machine would

have more overall license to be every bit as tawdry and smutty as the source novel.

|

| Naughty, Naughty |

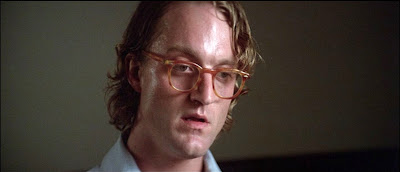

At last, the newfound permissiveness in movies allowed gay characters to be acknowledged as such, and they weren't required to die before the final reel (although they usually did, anyway). For movies that sought to be daring and hip, the inclusion of gay characters—always depicted as stereotypically as possible—was shorthand for provocative, taboo decadence. Here we have David Hemmings, in full flame with a cigarette holder, as fashion photographer Jerry Nelson and his blow-dried inamorato, British Shakespearean actor Alfie Knight (portrayed by Clinton Greyn).

In the minds of many, there also existed the misguided belief that The Love Machine was going to be a better film than Valley of the Dolls. Why? Well, putting aside for a moment the obvious...that it would be hard to make a movie that could be worse, it was Jacqueline Susann herself (who had never made secret her dislike for the movie version of Valley of the Dolls ) who promised fans that both she and her husband, Irving Mansfield, were taking steps to guarantee that they both would have creative input in bringing The Love Machine to the screen.

Indeed, thanks to a lawsuit filed by Susann against 20th Century-Fox and Beyond the Valley of the Dolls (1970)—that unofficial, unauthorized, non-sequel—Susann and Mansfield were able to take

The Love Machine to the more lucrative and contractually friendly pastures of Columbia Pictures. Columbia paid Susann $1.5 million for the film rights and granted her a possessive author's

credit for the movie's title (Jacqueline Susann's The Love Machine). With her husband installed as executive producer (apt enough, given that he was a TV producer by profession and

The Love Machine was set in the

television industry), this time around, the Susann-Mansfield household held a slightly tighter grip on the creative reins of bringing Susann's bestseller to the screen.

|

| The Hitchcock of Coarseness Jacqueline Susann makes another cameo appearance in one of her films. (That's LA newsman Jerry Dunphy on the left) |

Possessive film titles like Jacqueline Susann's The Love Machine are almost always clumsy and invariably rooted in contract perks, ego-stroking, and product branding. But like a Good Housekeeping seal of approval, an author's name attached to the title also implies that the film will be a more accurate, authentic realization of the writer's intent and vision. Well, as anyone can attest who's seen Stephen King's abominable self-penned 1997 TV-movie adaptation of his novel, The Shining (he disliked the many alterations and omissions in Stanley Kubrick's 1980 film), an author's participation in the adaptation of their own work is in no way a reliable guarantor of anything resembling quality. Or even watchability.

|

| John Phillip Law as Robin Stone |

|

| Dyan Cannon as Judith Austin |

|

| David Hemmings as Jerry Nelson |

|

| Jodi Wexler as Amanda |

|

| Maureen Arthur as Ethel Evans |

Like most of Jacqueline Susann's characters, Robin Stone

is allegedly based on a real-life individual. In this instance, the late CBS TV executive James T. Aubrey—the man we can thank for The

Beverly Hillbillies and a host of other fragrantly lowbrow moneymakers during the '60s. Like his movie

counterpart, Aubrey is said to have been a calculatingly shrewd cookie who held

the TV-viewing audience in the lowest contempt and made a fortune banking on the public's insatiable

appetite for mediocrity. Judging by the popularity of today's Jersey Shore/Kardashians train wrecks, you can't say the guy wasn't something of a visionary.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

My fondness for a specific brand of bad film is as difficult

to explain as it is to defend. It's not like I just get off on making fun of

them. On the contrary, most of these films are very professional, technically well-made

films in every regard. What I think I respond to is that scary zone in the

creative arts where the attempt fails to match the execution. That twilight zone where all the talent,

creativity, and hard work on one end somehow yields the 100% opposite

of what anyone intended. It fascinates me because it can occur at

any moment, no matter how heavily the deck is stacked for success. For example, consider Marlon Brando

putting cotton in his cheeks in The Godfather. That could have

turned out disastrous, but instead became iconic. Or what about Al Pacino's Cuban

accent in Scarface. What an enormous risk that was! It would have derailed the entire picture if audiences found it ridiculous and started to chuckle whenever he spoke.

|

| No, this isn't a shot of Robin Stone visiting Pee Wee's Playhouse. This is just a horrific example of chic '70s decor. |

I'm pointing out that the collaborative art of film is often like a dance on a wire; fiasco or triumph is sometimes based on tiny, intangible miscalculations or moments of blind overconfidence. Something that might not even be visible until after the film is already in the can. Hindsight makes it seem like an overripe performance or a particular narrative miscalculation could somehow have been avoided, but that's not true. It's the whole crapshoot element of it all that fascinates me.

If it's true in life that we learn most from our failures, I also believe there are similar lessons to be gleaned for the film buff confronted with a well-intentioned mess. When you watch a film that costs millions, involves hundreds of decisions, hours of hard work, the collaboration of many talented individuals...and the result is sometimes deplorable, you're staring straight into the face of the elusiveness of excellence. That or perhaps hubris, too many cooks spoiling the broth, or maybe (worst of all) professional cynicism: films that don't really care if they're good, so long as they make money.

|

| Ambitious Robin Stone goes head-to-head with network programming executive Danton Miller (Jackie Cooper) |

The Love Machine tries to be a hard-hitting, cynical, claw-his-way-to-the-top drama along the lines of The Sweet Smell of Success and The Young Philadelphians, but for all its faddish clothes, bare bosoms, and cuss words, it's fundamentally a creaky Fannie Hurst melodrama. It strives hard to be sensational and daring, but its focus needs readjusting. The story is too shallow to be good character drama, and its depiction of the inner workings of the TV industry is too superficial and cliche-ridden to serve effectively as expose. Even with all this considered, The Love Machine still manages to be a curiously addictive viewing experience, if only due to its utter cluelessness as to how airless and old-fashioned it is.

|

| The real star of The Love Machine is Robin's collection of blue bathrobes. It got so that I started to miss them if they failed to show up in a scene. |

PERFORMANCES

The likeable late actor (and last-minute replacement) John Phillip Law portrays Robin Stone with startling ineffectualness. Last seen sporting angel's wings and a feathered diaper in Barbarella, Law, who by all accounts sounds like a terribly nice guy in real life, latches onto Robin Stone's closed-off, inexpressive side and gives a performance that's too stiff even for a character referred to as a machine. He's given no help from the script, whose risible dialog suits the actor's robotic delivery. I've read that Jacqueline Susann (ever the fantasist) wanted Sean Connery for the role.

Dyan Cannon has always been a favorite of mine, but her performance here (no great shakes, but heads above the rest of the cast) is consistently undermined by the jaw-dropping, high-fashion get-ups she's called upon to wear. Given that she's not really provided a believable character to play, her bizarre fashion sense always takes center stage. According to a Jacqueline Susann bio, Cannon was so struck by a case of the giggles during a preview of The Love Machine (inspired by both her performance and the film) she had to excuse herself from the theater.

In the movie Barbarella, Jane Fonda's title character makes the sound observation, "A good many dramatic situations begin with screaming." I've an observation of my own that's equally on-point:

A good many bad movies feature fashion shows. A parade of Moss Mabry's coif-centric costume designs amusingly pad out The Love Machine's running time.

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

For anyone finding the film hard going (it's relatively slow by today's standards), I beg you to stick around for the climactic "Hollywood party fight scene." Here Ms. Cannon (balancing 23 pounds of teased hair) finally abandons her heretofore starchy acting style and lets loose with that infectiously raucous laugh of hers, setting in motion a truly memorable free-for-all that should have become a camp highlight by now. Finally, in trying to top Valley of the Dolls' infamous wig-down-the-toilet scene, The Love Machine finally does something right.

THE STUFF OF DREAMS

When The Love Machine was first released to

theaters, I was a mere 13 years old. Too young to see the much-ballyhooed

motion picture but old enough to take my mom's paperback novel to school and

pore over the "dirty parts" with my schoolmates. I'm not sure

what my problem was at such an early age, but I was very much taken with this sleazy novel. Particularly the iconography of the ankh ring Robin Stone wears on the paperback cover art. (In my defense, I grew up in San Francisco during the hippie era, and ankhs

were all over the place.) I also unsuccessfully tried to persuade my sister to buy

that Faberge "Xanadu" perfume that was cross-promoted in the film (ads for which recommended you mark "his" favorite spot with an "x").

|

| Xanadu by Faberge Samples were given away at many theaters showing The Love Machine |

2021 update

In spite of my unseemly youthful preoccupation with this movie, I

didn't actually see The Love Machine until I was well into adulthood. However, I'm happy to say that I wasn't disappointed. A little bored, perhaps (this movie takes itself WAY too seriously), but not disappointed. And while it's not nearly as much fun as Valley of the Dolls, The Love Machine has more than enough in the way of over-the-top fashions, poky dialog, and questionable performances to rank high among my favorite guilty pleasures.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011

|

| "...and when you put it on, you'll live forever. And love me forever." |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2011

.JPG)

.JPG)