For the most part, I don't see anything inherently wrong in a film morphing

from one kind of entertainment into another over the course of its "screening life." By this, I mean movies—a populist entertainment /art form presumed of

a certain marketable topicality at the time of their release, are, by nature, vulnerable

to the vagaries of time. A movie can start out as one kind of entertainment...say, thoughtful social drama...but, due to changing public tastes, evolve into something that gives pleasure to countless hundreds in new, totally

unexpected ways (i.e., unintentional humor or high camp).

|

| Rhoda Has Intimacy Issues |

Some movies, like John Huston's The

Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948) and George Stevens' A Place in the Sun (1951), feel as powerful today as I imagine when first released. Then there are those movies dismissed or misunderstood in their own time (Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, Orson Welles' Citizen Kane, Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter) that receive the benefit of revisionist reassessment.

But occasionally, a movie just seems to take its place in our collective consciousness as a work superficially cloaked

in the trappings of its time. Though they may be about such timeless human issues as love, death, survival, and hope, the matter in which those issues are addressed can brand the film as hopelessly dated.

|

| For Adults Only - No One Will Be Seated During the Last 15 minutes A "Catch Your Breath" Intermission at Each Screening! |

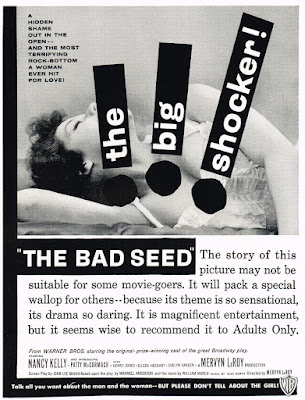

One of the earliest legit films to actively advertise itself as suitable for "Adults Only," The Bad Seed was taken to task for what many perceived to be its sensationalist and misleading ad campaign. Criticism was leveled at the film's advertising copy and graphics that hinted at sexual impropriety being at the core of the film's big secret ("The most terrifying rock-bottom a woman ever hit for love!").

Not surprisingly, the type of movies most susceptible to becoming relics of their time are those most determined to be daringly up-to-date upon release. A surefire recipe for instant obsolescence is to take over-emphatic, up-to-the-minute immediacy,

multiply it by sensationalism, and add a dash of self-seriousness. The

result is usually something so mired in a particular time, place, and mindset that it becomes near-impossible to take seriously in any of the ways originally intended.

|

| The Bad Seed's roots in old-fashioned theater are reinforced by its often stagy blocking |

When psychoanalysis was new, juvenile delinquency in its infancy, and post-war

conformity at its height, Maxwell

Anderson's Broadway 1954 play The

Bad Seed (adapted from the 1954 novel by William March) must have been

quite the eye-opener. A thriller about a sociopathic 8-year-old serial killer

sounds like a weed among the roses in a Broadway season that saw the premieres

of Peter Pan and The Pajama Game. But the chillingly

original premise and, by all accounts, remarkable performance of little 9-year-old anti-Shirley Temple, Patty McCormack, made The Bad Seed into a solid hit. Co-star Nancy Kelly won the Tony

Award for Best Actress that year. And in a rarity for Hollywood, virtually the

entire principal cast of the play was recruited to recreate their roles for the 1956 film

adaptation.

|

| Nancy Kelly as Christine Penmark |

|

| Patty McCormack as Rhoda Penmark |

|

| Eileen Heckart as Hortense Daigle |

But not everything that plays well across the footlights survives the magnification

of the movie screen. Suffering from a perhaps too-faithful adaptation that had

characters standing around talking for fitfully long stretches while

engaged in a lot of theatrically fussy "stage business." The combination of the minimal action and close-up lens trained on The Bad Seed only served to amplify the dubious

premise of its plot (hereditary homicidal tendencies) while failing to add much in the way of either verisimilitude or spontaneity to the progressively melodramatic proceedings.

|

| Henry Jones as Leroy Jessup |

|

| Evelyn Varden as Monica Breedlove |

|

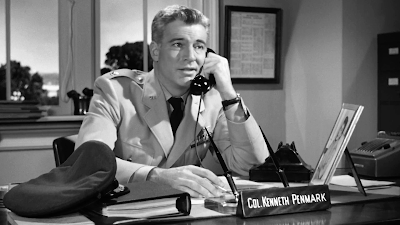

| William Hopper as Kenneth Penmark |

Navy Colonel Kenneth Penmark and wife Christine seem to have the ideal

child in their little Rhoda: an angelic, near-perfect package of pigtails and

ruffles, blessed with girlish grace and good manners. But, when Kenneth is called

away to Washington for business, Christine (who appears to be wound a little tight from the

get-go) begins to suspect that Rhoda's immaculate façade isn't perhaps masking

a more disturbed, darker personality dysfunction. The mysterious death of a local schoolboy and

Christine's epiphanic discovery of her birth lineage lead her to believe

that little Rhoda might be a budding serial killer: a possessor of a hereditary "bad

seed" gene passed on to Rhoda by Christine herself. What to do? What to do? What to do?

|

| Al Hirschfeld |

I make light of the preposterous-sounding premise, but quite honestly,

when removed from the gimmicky "serial killer gene" plotline, The Bad Seed is pretty solid thriller

material. It might have even tapped into the post-war/ McCarthy-era "banality

of evil" zeitgeist of Invasion of the

Body Snatchers (released the same year) had it managed to sidestep the theatrical

histrionics and showed more faith in presenting a dark vision of idealized suburban

perfection.

The Torment of Truth

|

| Paul Fix as Christine's father, Richard Bravo -telling her she might want to table those plans for a family reunion- |

The Bad Seed was a sensation on stage, but almost too much for the screen. The play's original twist ending had to be retooled so that evil didn't prevail, plus a tacked-on coda was introduced that had the entire cast return (even those who didn't survive) to give the screen equivalent of a curtain call bow. When I was a kid and The Bad Seed scared me senseless, this "See, it's only make-believe!" addition did what it was supposed to do; save the film from being too disturbing and grim.

As an adult, that silly roll call ending just feels like such an odd choice, the way it wrenches you out of the drama before you're even ready.

Topically The Bad Seed benefits from the uniqueness of its narrative perspective. Though horror movie screens overflow with little monsters now, I can't readily think of another film before this that dared deal with the topic of a child being capable of murder. Despite this novelty, The Bad Seed is

ill-served by how deeply the plot (and far too much of its dialogue) is entrenched in then-novel, now-outmoded Freudian psychological

theorems. As a result, a great deal of emotional drama gets submerged beneath reams of expository dialogue. And while the suspense and tension are generally well-handled, its overall effectiveness is undermined by some of the performances' overwrought and overrehearsed theatricality.

|

| Joan Croydon as Miss Claudia Fern Clearly, Miss Fern already harbors suspicions about Rhoda. But isn't that always the way...the parents are always the last to know their kid's a homicidal maniac |

I couldn't have been much older than Rhoda when I first saw The Bad Seed on TV (which is also likely the last time I ever took the film seriously), and I recall it being quite the shake-up experience. I was

raised in a middle-class neighborhood where kids were brought up to be seen and not heard. To be obedient and polite, to say "Please" and "Thank you," and to never,

but NEVER speak back to grownups. So it shocked the hell out of me to see a

little girl who could have stepped out of an episode of Father Knows Best or Leave it

to Beaver behaving so monstrously. The idea that a kid could exert any power over their own lives at

all was alien enough, let alone plan and carry out vicious murders with nary a

trace of remorse.

|

| Jess White as Emry Wages / Gage Clark as Reginald Tasker |

Although I was a fan of horror movies as a kid and loved to be scared, I must say I didn't mind that the deaths of little

Claude Daigle or handyman Leroy were never shown in The Bad Seed. My fertile imagination furnished all the gory details. I remember being

very torn up by the grief of Eileen Heckart's Mrs. Daigle, and the sound of the

gunshot near the end nearly sent me flying off the sofa. My strongest memory is of Rhoda's final trip to the boathouse. It was spooky enough that she

was out alone at night in a rainstorm, but I thought maybe her maddeningly

clueless father would wake up and catch her red-handed with the medal. That bolt of lightning hit me like ...well, a bolt of lightning. OMG! I had NEVER seen a

kid killed in a movie before, and that image stayed with me for many a

nightmare.

Youth and naiveté definitely have their advantages with some movies, so at least I

get to say that I had one pure, unironic experience of The Bad Seed before the unintentional laughs set in and The Bad Seed, almost imperceptibly, went from serious to hilarious

in my eyes.

Granted, the film's pitch had always been a little high, but with

maturity, the passing of time, and changing tastes, The Bad Seed started to look as dated and reactionary as one of

those "social guidance" films of the '50s and '60s.

The patent phoniness of Rhoda's "good little girl" act is so obvious it instantly brands the adults in the film as idiots. However, it also simultaneously turns Leroy into the film's clear-eyed hero and the collective voice of the viewing audience. Happily, the gradual inability to take The Bad Seed seriously only made the film more watchable, not less.

|

| "Have you been naughty?" |

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

In real life, it takes little effort for me to see most children as monsters. But making them look menacing on the screen is extremely difficult. The 1976

film The Omen neatly sidestepped the pitfall

the wan 2006 remake fell into (headfirst) by framing the action in ways that left the child's evil nature ambiguous. In the original film, the child behaves normally, leaving the audience to project whatever it wanted onto his angelic, inexpressive pan. In the remake, someone got the bright idea to have the child actor perpetually scowl and glower into the camera...the result being the surely-unwanted

effect of making it look like little Damien is perpetually suffering from a devil of a tummy ache. What makes Patty McCormack so memorably creepy in The Bad Seed is that she's like a schoolyard bully dreamt up by Murder, Inc.

The only reason this scene gets laughs is that Patty McCormack is scarier than hell in it. Who'd ever think a little girl in pigtails and a pinafore could make the hairs on the back of your neck stand up?

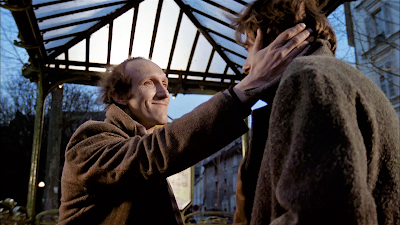

These days, when the bratty behavior of children is endorsed, encouraged, and regarded as business-as-usual in

every sitcom and movie comedy, I wonder if a film like The Bad Seed would even work today. Indeed, the superb thriller We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) is an excellent example of how a "bad seed" scenario can be handled in a serious and dramatically compelling way.

But Rhoda Penmark is both a product of her time and a victim of it.

The ladylike decorum expected of little girls in the '50s is so passe, everything about Rhoda comes across as anachronistically comic, severely undercutting her intended menace. In movies today, little girls who look like Rhoda Penmark are the victims of girls who look like Wednesday Addams.

|

| Monica Breedlove, the Freudian landlord, is a particular favorite of mine. |

The gift that keeps on giving when I watch The Bad Seed now is that Rhoda's brattishness calls to mind so many pop-culture icons of bad behavior...like Neely O'Hara and Alexis Carrington. Her outbursts and threats make me giggle, not just because one doesn't expect such malevolence coming out of a child kitted out to resemble a Chatty Cathy doll, but also because she's carrying on in a way we've long come to associate with grown-up entertainment industry brats and divas. Rhoda is rude, ruthless, selfish, self-involved, single-mindedly

determined to get what she wants, and impervious to the suffering of others. I'm thinkin' Madonna or Kanye West.

|

| The Original Material Girl |

PERFORMANCES

Nancy Kelly and Eileen Heckart give the kind of robust, herculean performances

that usually garner Oscar nominations, and indeed both (along with McCormack) were, in fact, nominated for Academy

Awards. Both are really very good, though neither actress lets up "acting"

for even a second. Kelly's stylistic excesses and singsong way of conveying sincerity may

induce laughter, but her character's anguish is really affectingly played. Heckart has some great material to work with, and much of it she plays

with real poignance. But a little too much theatrical "drunk" shtick creeps into

the characterization for it to avoid the occasional lapse into overkill.

The film's true star...and what an absolute marvel she is...is 10-year-old Patty McCormack. Although her performance is over-rehearsed to within a hairsbreadth, her Rhoda is an alternatingly chilling and hilarious characterization that has deservedly become iconic. An audaciously dark depiction of youthful duplicity—imagine Leave it to Beaver's Judy Hensler as a serial killer—Rhoda absolutely refuses to listen to anyone's drummer but her own. The way she exploits and subverts the expectations of traditional gender roles to her personal advantage feels like an act of guerrilla rebellion against the impossible image of female perfection and passivity she only superficially embodies. Rhoda Penmark is one of cinema's classic villains.

|

| Leroy, Sex Bomb In much of The Bad Seed's intentionally misleading publicity campaign, Leroy, the maintenance man, was presented in the context of some kind of sexual indignity suffered by the heroine |

THE STUFF OF FANTASY

No longer a viable suspense thriller (not for me, anyway), The Bad Seed does work remarkably well as a satirical

black comedy of American paranoia in the mid-'50s. McCarthyism took root when post-war America was just starting to look within its own backyard for threats

to the so-called "American Way of Life." What did it find? Well, juvenile

delinquency, for one. And what else is Rhoda but a steely-eyed juvenile

delinquent in Mary Jane shoes? (OK, a juvenile homicidal

delinquent, but I'm trying to make a point.) As the perfect little angel who'll

stop at nothing to get that coveted Penmanship Medal, Rhoda is camouflaged anarchy let loose on idealized "normalcy."

Like many a con man, crooked politician, or gangster throughout history, Rhoda manages to get away with murder

(heh-heh) by presenting a false but reassuring front of conformity. Everyone is so slow

to pick up on the rather obvious clues of Rhoda's guilt because….well, little

girls just don't do that sort of thing. The reliability of appearances and the rigid adherence to societal roles were very real in the '50s, making it easier to accept that everyone buys into Rhoda's too-good-to-be-true act.

The screenplay of the wholly forgettable 1985 TV remake of The Bad Seed failed to consider how much society's perception of childhood had changed post-Rosemary's Baby, The Omen, and The Exorcist, making the updated version come across as more antiquated than the original.

A better remake, in spirit, if not in actuality, is The Good Son, a 1993 against-type departure for the unaccountably popular Macaulay Culkin.

|

| You Gon' Die |

Despite its daringly original premise and first-class credentials, I'm

afraid the movie that once promoted itself as "The most shocking motion picture

ever made!" containing "The most chilling moment the screen has ever unleashed!"

is, for me, now mostly an enduring camp staple. And though I'm aware that The Bad Seed continues to freak out entirely new generations of first-time viewers fortunate enough to catch it while they're still of an impressionable age (before their cynic genes kick in), my joy comes from familiarity. Make that overfamiliarity.

I still watch The Bad Seed often, each viewing being a somewhat home-grown MST3K experience where my partner and I talk to the screen, recite lines of dialogue, and affectionately laugh at the self-seriousness of it all.

In her adult years, actress Patty McCormack has embraced The Bad Seed's cult/camp status. She frequently appears at

screenings, judges Rhoda look-alike contests, and answers questions about making the film (her DVD commentary offers a wealth of behind-the-scenes info). Mining the camp factor, the play version of The Bad Seed has become a favorite of 99-seat theater productions, often with an adult male cast as Rhoda. People seem

to have a deep affection for The Bad Seed, either due to childhood exposure to the then-frightening film, or a later-in-life cult appreciation for the way the laughs come at the expense of the film's sincere over-earnestness and '50s mindset, not the performances.

Some time ago, I saw a stage production of The Bad Seed and was surprised to discover that one of the big shocker set pieces of the play was a nocturnal walk through the house by a restless Christine after the death of Leroy. It's a stormy night full of thunder and lightning, and as Christine moves to close an open window, a flash of lightning reveals the charred corpse of Leroy lunging out at her. It must have been a big "gotcha" moment back in its day. But on the night I attended, the actress playing Christine had so much trouble lifting the window blind, she was ultimately obliged to politely hold the stubborn curtain aside to facilitate her own persecution. Matters weren't helped by Leroy missing his key light, leaving him thoroughly in the shadows, resulting in Christine appearing to be engaged in hand-to-hand combat with her living room curtains.

|

| The Bad Seed opened on Broadway on December 8th, 1954 |

BONUS MATERIAL

Popping up now and again on YouTube and definitely worth the watch is the fabulous 1963 Turkish remake of The Bad Seed titled Kötü Tohum. Starring real-life mother and daughter Lale Oraloğlu and Alev Oraloğlu, it's a very well-made adaptation that hews closely to Maxwell Anderson's play but deviates from it in the most compelling ways.

More shocking than anything you'll see in the film itself is this bit of mind-blowing behind-the-scenes cheesecake showing prim Nancy Kelly keeping the crew "entertained" between setups (more likely, giving her gams some air on the hot set). Meanwhile, Joan Croydon (Miss Fern) fails to get into the spirit of things.

Possibly the most egregiously off-the-wall of the many misleading ads concocted to market what was apparently very a difficult-to-market movie. Seriously, what were they thinking when they dreamed this one up?

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2012

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)