Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures (Revised Edition) by J. R. Jordan - 2020

|

The Pause That Refreshes.

Director Robert Wise hoists a Coca-Cola on the set of West Side Story with the film's star Natalie Wood. Wise co-directed West Side Story with choreographer Jerome Robbins, their twin 1963 Oscar win for Best Director was the first time the directing award had ever been shared. (Photo not featured in book.) |

By rights, the director of the movie that

single-handedly saved 20th Century Fox from bankruptcy should be as well-known as John Ford or Howard Hawks. And if that same fellow received

his first of seven career Academy Award nominations (four wins) for editing one of the most highly-acclaimed

motion pictures in American cinema, you'd think he'd be at least as talked and written about as William Wyler or George Cukor. Now, what if this guy was also responsible for two of the most iconic movie musicals of all time...films that made a fortune for the studios, garnered Best Picture Oscar wins for both, and influenced the way movie musicals were made for years after...surely this director must be as famous as Orson Welles or Alfred Hitchcock. Right?

Answer: Well, not so much.

|

The Sound of Music

Even die-hard devotees of the film have a hard time remembering who directed it. |

Of course, the person I’m referring to is the late director-producer

Robert Wise (1914 – 2005). It was Wise’s adaptation of the Broadway musical The

Sound of Music (1965) that rescued 20th Century Fox from the

threat of Cleopatra (1963)-induced bankruptcy. It was Wise who, at the

ripe old age of 26, edited the Orson Welles masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941) and received his first Oscar nomination. (Wise was also the person controversially tasked with whittling/butchering Welles' The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) down to 88 minutes from its original 148-minute running time.) And in 1962 and 1966, it

was Robert Wise who each year took home Oscars for Best Picture and Best Director in recognition for his work on West Side Story and The Sound of

Music respectively.

|

West Side Story

According to the Jerome Robbins biography Somewhere, Robert Wise was "quite reluctant" when asked to co-direct with the Tony Award-winning choreographer/director of the original 1957 Broadway production. An agreement was struck granting Robbins control of the musical sequences, Wise the book scenes. Even with this, the producers fired Robbins some 45 days into the film's 7-month shooting schedule, citing his over-meticulousness as the cause for the film being severely and expensively behind schedule. |

Having directed some 40 motion pictures throughout his six-decade career—several now regarded as contemporary classics—Wise is hardly an unknown in film circles. Similarly, given the many

positions of honor he held in his lifetime (president of both the Academy of

Motion Picture Arts & Sciences and The Director’s Guild) and the number of industry

trophies bestowed upon him (the aforementioned four Academy Awards, The Irving

G Thalberg Memorial Award, The Director’s Guild D.W. Griffith Award, and The AFI

Life Achievement Award), Wise isn’t even a filmmaker about whom it can be

said had a career that went unrewarded.

|

Two for the Seesaw

Wise uses space to dramatize the isolation of characters played by Shirley MacLaine & Robert Mitchum |

The boon and bane of Robert Wise’s career has always been his

versatility and disinterest in imposing a defining “A film by Robert Wise” signature

on his movie.

“Some of the more esoteric critics claim there is no

Robert Wise style or stamp. My answer to that is that I’ve tried to approach each

genre in a cinematic style that I think is right for that genre.” -

Robert Wise The Los Angeles

Times 1998

The range of genres Wise worked in is staggering. Film-Noir:

Born to Kill (1947) / Western: Blood on the Moon (1948) / Sports:

The Set-up (1949) / Comedy: Something

for the Birds (1952) / War: Destination Gobi (1953) / Bio: I Want

to Live (1958) / Crime: Odds Against Tomorrow (1959) / Romance: Two

for the Seesaw (1962) / Adventure: The Sand Pebbles (1966) / Musical:

- Star! (1968) / Horror: The Haunting (1963) / and Sci-Fi: Star

Trek: The Motion Picture (1979).

|

The Hindenburg

Suspicious-looking onlooker Roy Thinnes skulks behind Colonel George C. Scott and Countess Anne Bancroft, whose opium addiction has her airborne long before the dirigible ever leaves the ground. |

And while Robert Wise may not have been the most hands-on director, his films led many a performer to Oscar wins and nominations (Steve McQueen received his only Oscar nomination for The

Sand Pebbles).

—From the book Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures by

J.R. Jordan—

René Auberjonois on working with Wise on The Hindenburg

(1975): “But I have very little recollection of Robert directing me as an

actor. And that is unique, really. I didn’t have much of an actor-director

relationship with him.”

Janette Scott on working with Wise on Helen of Troy

(1956): “From our perspective, he didn’t really direct. He would place us

and say things like, ‘Let's try it.’

|

The Day the Earth Stood Still

Michael Rennie (left) no doubt feeling ill. |

Historically speaking, if Wise suffers from anything, it's from a lack of legacy. He's a director with

no visibility (there aren't any Alfred Hitchcock-like walk-ons in a Robert Wise movie); no public persona (he didn't make the talk-show circuit like Otto Preminger); no mystique (there are no juicy anecdotes detailing displays artistic temperament); and impossible to "type" (versatility resists branding). When film enthusiasts and scholars talk about the directors of the studio

system era, the name Robert Wise is conspicuous in its absence. Underrated and

overlooked in comparison to his peers, Robert Wise is the Jan Brady of film

directors. The Rodney Dangerfield of Cinema.

|

Photo: Los Angeles Times Robert Wise's reputation as a director worthy of scholarly evaluation took a serious blow in 1968 when influential film critic and Auteur Theory advocate Andrew Sarris summarily dismissed the versatile director as a "technician without a strong personality," and claims that Wise's stylistic signature was "indistinct to the point of invisibility." |

Hoping to rectify this is the book— Robert Wise: The

Motion Pictures by J.R. Jordan, originally published in 2017 and now available

in a revised and updated edition. Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures is a well-researched, sizable volume

(506 pages) that takes a comprehensive, chronological look at the full body of

Robert Wise's career output as a director. All 40 of Wise’s feature films are highlighted,

including his last, a TV-movie filmed when the director was 85-years-old.

The book is divided into five sections, each representing a significant period in Wise’s career (section titles are the author’s, the descriptors my

own):

RKO Pictures – B-movies under the tutelage of horror master Val

Lewton.

The Fifties – His most prolific period.

Primetime – The ‘60s, his most successful decade.

The Science and Surrealism of the Seventies – Big budgets &

modest returns.

Twilight – His brief return to filmmaking following a

10-year absence.

|

The Haunting

My favorite Robert Wise film is also one of the most effective haunted house films I've ever seen |

An entire chapter is devoted to each of Wise’s films. The chapters

comprise a thematic quote; plot description; details about the making of the movie;

trivia and behind-the-scenes-info; pertinent screen dialogue; and in some

instances, interviews with actors and other individuals involved in the production. More than 20 interviews were conducted for the book, among those contributing their

thoughts on working with Wise are Marsha Mason (Audrey Rose), George Chakiris

(West Side Story), Lindsay Wagner (Two People), René Auberjonois

(The Hindenburg), Earl Holliman (Destination Gobi), Billy Gray (The

Day the Earth Stood Still), and Janette Scott (Helen of Troy). For me, these interviews are an entertaining and informative highlight.

Featuring an index, bibliography, and where necessary, citation

footnotes, it’s a book that can be read cover to cover (as I did) or used for reference.

|

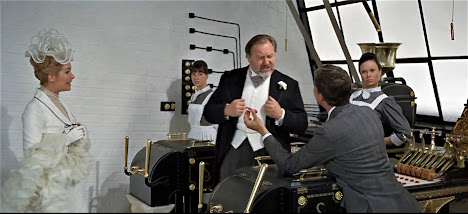

Star!

When it came to Wise's return to the musical genre, three failed to be the charm. The expensive, tuneful, and colorful musical biography of Gertrude Lawrence was as big a flop as The Sound of Music was a hit.

|

Because so many of Robert Wise’s movies are so well-known

and popular, yet Wise remains a director about whom little has been written, it’s

natural to approach this sizable volume with a great deal of expectation. (In

my case, over-expectation. I’m a big fan of Robert Wise, but the last book I

read about him was back in 2007…Richard C. Keenan’s The Films of Robert Wise.) So, at this

point, I need to emphasize that one's enjoyment of Robert Wise: The Motion

Pictures will be significantly enhanced by understanding clearly what the

book is and what it isn’t.

|

Odds Against Tomorrow

Produced by Harry Belafonte and credited as the first film-noir to star a Black actor

|

Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures

is not an academic work of film scholarship and doesn’t present itself as such. More

an appreciation and career tribute to Wise, Jordan approaches his subject with

a film-buff’s enthusiasm and a well-informed informality. Biographical

information about Wise, personal or professional, is minimal, the emphasis being

on letting the films speak for themselves, letting actors and industry

professionals share their thoughts on working with Wise, and highlighting each

film’s production and content. As per the latter, perhaps an overabundance of

riches. Unaccountably detailed plot descriptions dominate the book, it not

being unusual for 5 pages of a 9-page chapter to be devoted to the recounting

of a film’s storyline alone.

|

Audrey Rose

Marsha Mason and John Beck wonder if the reincarnated can reverse charges

|

For me, Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures succeeds as

an introduction and primer for those unfamiliar with the director, and as a solid

reference book supplement to the already existing books about Robert Wise (I’m

only aware of their being 5 total). I would think this book would prove very useful in this age of streaming sites and online movie accessibility, its chapter-by-chapter highlighting of each film serving as a guide for the unfamiliar, a recap to the initiated.

Should there be a 2nd revised edition of Robert Wise: The Motion Pictures, I hope the opportunity presents itself for a strong editor to tighten up the prose a bit. There's so much worthwhile in Jordan's book, yet I suspect its form as is might keep well-read cinema enthusiasts away. It's great to have a book dedicated to the entire body of Robert Wise's directing career, even better to encounter such a sincere tribute to a man who, by all accounts, was an unusually kind, principled, and self-effacing director whose movies continue to touch many lives.

|

The Andromeda Strain

You know it's science fiction when Paula Kelly and James Olson battle an uncontrolled

outbreak of a deadly virus and there's no one around bitching about having to wear a mask.

|

Indeed, the

major through-line of each and every interview conducted in the book can be

found in this quote by a pre-The Bionic Woman Lindsay Wagner, whom Wise directed

in her first film Two People (1973):

“Robert (Wise) to this day remains one of the nicest, most

gracious film directors I’ve ever encountered. Consequently, my indoctrination

to the business was that power, success, and kindness can all coexist. Because

to me, those are the characteristics that defined Robert Wise.”

The author provided a review copy of the book.

All screencaps are from Robert Wise movies in my personal DVD collection.

|

Simone Simon and Ann Carter in The Curse of the Cat People (1944)

Taking over the reins from original director Gunther von Fritsch, this RKO film

produced by Val Lewton marks Robert Wise's debut as a film director. |

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2021