|

| Never Turn Your Back on a Patient |

Of the seven films that make up Amicus Productions' complete catalog of horror anthologies—films released between the years 1965 and 1976—Asylum is my hands-down, all-time favorite. An opinion formed in my early teens based on then having only seen the five entries released in the 1970s: The House That Dripped Blood (1971), Tales from the Crypt (1972), Asylum (1972), Vault of Horror (1973), and From Beyond the Grave (1975). Now, many decades later and thanks to streaming services, it's an opinion reinforced and reaffirmed after finally getting to see those heretofore elusive first two titles in the Amicus anthology canon: Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965) and Torture Garden (1967).

Asylum, the 5th film in the series, is a creepy, clever chiller featuring four tantalizingly taut tales of terror written by veteran horror-meister Robert Bloch (

Psycho,

Strait-Jacket) from his own short stories first published in volumes of

Weird Tales Magazine (one dating back as far as 1936).

Directed by Roy Ward Baker (who guided Marilyn Monroe through one of her earliest dramatic roles in Don't Bother to Knock - 1952) and evocatively lensed by British New Wave cinematographer Denys Coop (A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar), Asylum remains an engagingly written, intriguingly well-cast, ceaselessly entertaining example of the portmanteau horror film at the peak of its form. These modestly-budgeted films, made on the quick and slated for quick playoffs at Drive-Ins and on horror show double-bills, vary, as they must, in quality (Asylum took all of 24 days to film, and was the second of two Amicus anthologies rapidly released in the same year). But for my money, of the entire Amicus septet, there isn’t a clunker in the bunch.

|

| You Have Nothing To Lose But Your Mind |

Britain’s Amicus Productions (which, until very recently, I always confused with UK's then-reigning studio of gothic horror, Hammer Films) majored in the omnibus, multi-story horror film. These stories-within-a-story journeys into the macabre followed a standard format, presenting four or five unconnected tales of the weird and unexpected…some darkly comic, but always incorporating violence, the occult, or the supernatural… within a unifying framework that itself offered some kind of final revelation or surprise payoff.

The root of my attraction to these Amicus anthologies can be directly traced to my older sister. Her healthy taste for the macabre gave her a love of the cartoons of Charles Addams, which led to my being introduced to the works of Edward Gorey and the word “ennui” via her copy of

The Gashlycrumb Tinies, and fostered a pretty impressive horror comic book collection. With titles like

The Witching Hour and

Weird Mystery Tales, these magazines often scared the daylights out of me (a story about a little girl whose parents refuse to believe there’s a “thing” hiding in her close, had me sleeping with covers over my head for years), but that didn’t stop me from making a pest of myself asking to be the first in line to borrow it whenever she brought a new issue into the house.

It may sound weird that I enjoyed scaring myself like I did, but I think adults sometimes forget how boring childhood and adolescence can be. The regimentation of school, homework, chores, and the constancy of babysitting (sittee to sitter in a flash of an eye) fuels a hunger for “safe” sensation. Whether in the form of playground requests to be pushed higher or spun faster, laugh-screaming at home from startled by siblings jumping out at you from dark rooms, or watching one of the many horror anthology programs running on TV at the time (

The Twilight Zone,

One Step Beyond, Journey to the Unknown, etc.)…the objective is surprise and excitement. Being scared is just one mode of getting there. And as any kid can tell you, being intermittently frightened can be the most fun a kid can have without getting into trouble.

Many horror films today, finding revulsion far easier to elicit than genuine fear, wind up leaving no impression on me at all with their impotent gore and lazy jump cuts. By contrast, the Amicus anthologies were supremely adept at creating spooky horror without being disturbing or gross. No matter how grisly things got, dastardly deeds were more often suggested than depicted. Sure, most of the scares were tame even by ‘70s standards, but these movies stayed in my mind for a lifetime because the filmmakers understood the elemental entertainment value of a really good scare.

In the ‘70s, when antiheroes and unsettlingly tragic endings in movies were virtually compulsory, the Amicus anthologies, which operated on the moral code of fables and fairy tales, appealed to my youthful sense of fair play. In narratives that pivoted on revenge or comeuppance arriving in the form of an unforeseen twist…ironic or karmic…at fadeout, evil was always punished. Fate would take its cue from Gilbert and Sullivan and mete out gruesome punishments to fit the various crimes. While the movies were playing, the unimaginable and horrific had a field day. But by the closing credits, the world of order had been safely righted again.

|

| The Dunsmoor Asylum for the Incurably Insane |

Perhaps because as a teenager I found real life to be plenty terrifying as it is, thank you, I never really went in for the gothic horror of vampires, werewolves, or Frankenstein’s monsters. I could relate to the fantasy, but the worlds these films took place in were at such a remove, I was never engaged enough to be scared.

What appealed to me about the Amicus anthologies was that they were set in the present day, featured a kind of vibrant color photography I usually associated with musicals, and tended to reference gothic horror traditions through a contemporary, ofttimes wry, prism (“The Cloak” episode of

The House That Dripped Blood). The narratives were marvels of storytelling economy, the best of them incorporating my favorite “modern gothic” trope: the collision of the worlds of intellect and the supernatural/occult (a la

Rosemary’s Baby). I’m peculiarly intrigued by stories wherein pragmatic "

There’s a logical explanation for that!” types are forced to confront the possibility that there may be things that exist beyond the borders of science and reason.

Asylum's wraparound story has a reasoned, methodical doctor armed with unwavering certainty that the damaged psyche is a frontier that can be tamed, coming face-to-face with a situation not covered in psychiatric journals. My kind of movie.

|

| Robert Powell as Dr. Martin |

In a nice subversion of the gothic tradition,

Asylum opens not on a dark and stormy night with a horse-drawn carriage arriving at the gates of a dilapidated castle, but in the daylight with a sleek, red sports car speeding through a rainstorm to the gates of a contemporary mental facility that looks more like a menacing Victorian manor. Before the opening credits are over

Asylum has visually established its central conflict: Modern medical science, in the form of nattily-dressed, university-educated, compassionately humorless Dr. Martin (Robert Powell) vs the insensible ancient sciences long-familiar to horror movies—aka the paranormal and That-Which-Cannot-Be-Explained.

|

| Patrick Magee as Dr. Lionel Rutherford |

Applying for a position at the remote asylum, Dr. Martin is challenged to an unorthodox test by the current chief of staff Dr. Rutherford (Patrick Magee): identify which of the institution's patients is the former head of the institution, Dr. B. Starr. Two days prior, Dr. Starr suffered a violent mental breakdown and now exists in a hysterical fugue…identity absorbed into a new personality, name, and personal history. If Dr. Martin can ascertain which patient, male or female, was once Dunsmoor’s head psychopathologist, the job is his.

|

| Geoffrey Bayldon as Max Reynolds |

This intriguing trial sets up three of the film's vignettes as unreliably-narrated flashback tales told by the possible Dr. Starr candidates detailing how they came to be committed. The fourth story is interwoven with the film's wraparound narrative and unfolds in the present time.

The use of music is one way a horror film can tip its hand that it’s not taking itself all that seriously (the use of a harpsichord in Hammer’s

Die, Die, My Darling, for example). Asylum’s use of two stentorious orchestral pieces by 19th-century classical composer Modest Mussorgsky (“A Night on Bald Mountain” and “Pictures at an Exhibition”) work effectively in lending the film an appropriately ominous tone of chaotic dread wholly in keeping with the broad-strokes weirdness of the collected stories.

Will the real Dr. B. Starr please stand up?

The Four Bs: Bonnie, Barbara, Bruno, and Byron

Thanks to the internet (again), I finally had the opportunity to read the original Robert Bloch short stories that inspired these episodes. Bloch's adaptations for the screen are nicely updated while remaining faithful to the tone and themes.

FROZEN FEAR (Weird Tales - May 1946)

|

| Barbara Parkins as Bonnie |

|

| Richard Todd as Walter |

|

| Sylvia Syms as Ruth |

Lots of people would do anything to be with the beautiful, and here, psychopathically self-enchanted, Barbara Parkins (my first time seeing her since

Valley of the Dolls when I was eleven), but older, foppish, and very-married Richard Todd resorts to murdering voodoo-affiliated wife Sylvia Syms, chopping her to pieces, then storing the butcher-wrapped parts in a deep freeze in the basement. As grotesque as this scenario sounds, the whole “Till Murder Do Us Part” trope of spouses killing spouses was so overworked on TV by this time (every 3rd episode of

Alfred Hitchcock Presents it seemed) that this sequence had the most familiar feel to it.

But the supernatural twist of those frozen body parts reanimating to exact murderous revenge tips this delightfully demented horror escapade into mini-classic territory. Silent for nearly half of its running time, it's a virtuoso display of how tension and suspense can be created by wholly visual means. And something about those primitive special effects warms my chilly heart.

THE WEIRD TAILOR (Weird Tales - July 1950)

|

| Barry Morse as Bruno |

|

| Peter Cushing as Mr. Smith |

Impoverished tailor Morse is commissioned to make a suit out of a mysterious fabric by sad-eyed gentleman Cushing. The conditions of its manufacture are so peculiar and exacting one knows no good can come of it…and it doesn’t. An eerie atmosphere and fine acting propel this sequence which we learn from the DVD commentary was the segment Bloch was least happy with, owing to the extensive rewriting by producer Milton Subotsky that changed the tailor (a pretty reprehensible man in Bloch’s original story) into a sympathetic victim. A suspenseful mood piece that was not particularly scary to me even as a kid, it was my introduction to Peter Cushing. Was there ever such a class act? The expressiveness of his eyes is heartbreaking. The acting in this vignette is very strong, helping to gloss over my feeling that if anyone should have been driven insane by the events of the story, it's the tailor's wife, Anna (Ann Firbank).

LUCY COMES TO STAY (Weird Tales - January 1950)

|

| Charlotte Rampling as Barbara |

|

| Britt Ekland as Lucy |

My weakness for “Le femmes au Cinéma” is well-documented, so it’s likely to come as a surprise to absolutely no one that this is my favorite of Asylum’s four vignettes. Not just because of the rarity of having two women protagonists, but because of the particular women in question. We’re not talking Stefanie Powers and Donna Mills in a TV Movie-of-the-Week, folks…this is full-tilt, ‘60s iconic, international sex symbol/movie star talent & glamour courtesy of Charlotte Rampling AND Britt Ekland!! In the same movie! Together on the same screen! Seriously, only the pairing of Paul Newman & Robert Redford rivals these two in gorgeousness. This being my first time seeing either actress in a film, this segment fairly put me in a swoon back in 1972, but the story’s a kick as well.

Rampling returns home after a stint in a mental institution only to discover her mischievous friend Ekland is there to stir the pot of suspicion that Rampling’s superficially solicitous brother is actually angling to send her back to the institution for good so he can inherit the family home. When this Lucy says “I have a plan” I can assure you can bet it’s nothing like Lucy Ricardo ever thought up. The performances in this sequence are all first-rate, and the story (which took me totally by surprise) checks all the boxes of what I gravitate to in female-centric melodramas:

3 Women (1977),

Mortal Thoughts (1991),

Single White Female (1992

), and

Images (1974).

MANNIKINS OF HORROR (Weird Tales - December 1939)

|

| Herbert Lom as Dr. Byron |

Asylum’s final tale, about a demented (or is he?) former surgeon who constructs dolls in his own likeness that he insists he can bring to life with his mind, integrates with the film’s wraparound narrative of Dr. Martin making his final guess as to the identity of the real Dr. Starr. This sequence creeped me out because the nightmare fantasy of malevolent toys coming to life was one I harbored when I was very young and had one of those marching robots that ran on batteries. The film winds up with a nice twist that I’d actually forgotten when I rewatched this recently, so it’s nice to report that it’s effective as ever.

For reasons having as much to do with nostalgia as with the film's craftsmanship and irresistibly entertaining execution, Asylum for me still stands (and likely ever after remain) as one of the best if not THE best of the Amicus horror anthologies. It scarcely makes a false tiny step.

BONUS MATERIAL

The film most widely credited with popularizing the anthology horror film is 1945's Dead of Night from Britain's Ealing Studios.

|

| Dead of Night (1945) |

Five horror stories helmed by four different directors, this classic omnibus film is best remembered for the segment starring Michael Redgrave as a ventriloquist who comes to believe his dummy, Hugo, is villainously alive.

|

| Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965) |

Amicus Productions' first anthology film was Dr. Terror's House of Horrors directed by Freddie Francis. Starring Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, Max Adrian, and a young Donald Sutherland.

|

| Tales from the Hood (1995) |

The sharpest and perhaps my personal favorite of the contemporary horror anthologies is this inspired, Afrocentric update of the genre which effectively blends horror, comedy, and cutting social critique. Directed by Rusty Cundieff,

Tales from the Hood's four stories are a supernatural/occult take on the very real horrors of police brutality, white supremacy, child abuse, and gang violence. The framing device used is an eccentric funeral parlor director played with sinister glee by Clarence Williams III.

Bloch Party

In 1961 Robert Bloch wrote a more faithful adaptation of his 1950 short story "The Weird Tailor" for an episode of the horror anthology TV series Thriller hosted by Boris Karloff. Henry Jones starred as the tailor. Episode available for viewing HERE.

|

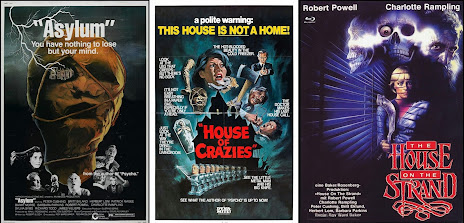

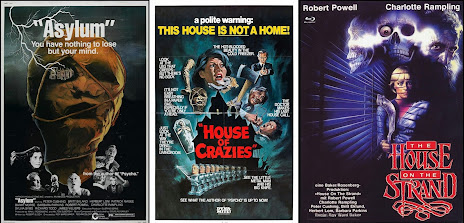

| click on image to enlarge |

One of the things I miss in this post-Blockbuster Video world is the I-can-smell-the-desperation artwork VHS/DVD covers resorted to in order to catch the consumer eye on overcrowded shelves in overlit outlets. With no time for nuance, the cover art relied on overstatement, exaggeration, and misdirection.

House of Crazies (center) was the artlessly blunt title selected when

Asylum was rereleased to theaters in 1979. Not only does the poster artwork contain a major spoiler, but it would seem Barbara Parkins didn't give permission to have her likeness reproduced, 'cause who in the hell is that woman at the top?

The German DVD release (right) went all gonzo and decided to be as misleading as fuck. First, by giving Asylum the nonsensical title: The House on the Strand. Then contributing random artwork that looks like a grown-up Patty MacCormack holding a scythe. Worse still, the top figure on the right is that insane Santa Claus from Tales from the Crypt.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2021