Spoiler Alert: Crucial plot points are revealed in the interest of critical analysis and discussion

“My Favorite American film.” François Truffaut

“One of the purest movies I’ve ever seen.” Michelangelo Antonioni

The Criterion Collection release #200 – DVD in 2003. Blu-ray in 2015.

I’m pleased The Honeymoon Killers has finally acquired the kind of mainstream critical acceptance and highbrow cineaste cachet it has always deserved. Precisely the kind of rep that should prevent the future unfamiliar and uninitiated from being scared away--as I was in 1970--by that Drive-In exploitation flick title. Sounding then to me like a movie that belonged on a double-bill with Werewolf in a Girl's Dormitory, I avoided The Honeymoon Killers for years, only finally getting around to seeing it when TCM aired it sometime in the early 2000s.

Originally to be titled either

Dear Martha or

The Lonely Hearts Killers when slated for 1969 release by low-budget independent distributor American International Pictures (of biker and

Beach Party movie infamy). When that deal proved short-lived, the small film (lensed in 1968 for $200,000) acquired the grindhouse-friendly title of

The Honeymoon Killers and was picked up for 1970 release by the somewhat more upscale Cinerama Releasing; an independent distributor specializing in handling high-profile niche-market films and arty genre movies (

They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?,

The Killing of Sister George).

The Honeymoon Killers opened in Hollywood on Wednesday, March 11, 1970, at the Fox Theater on Hollywood Blvd. Actress Shirley Stoler was in attendance on opening night to judge a "Fat is Beautiful" contest.

Released in many markets just before Valentine’s Day, The Honeymoon Killers, despite its "Creature Features" title and grisly ad campaign, was surprisingly well-received by critics at the time. But due perhaps to the limited marketing resources of Cinerama Releasing or the film’s overall grim subject matter, it proved to be only a modest success at the boxoffice and quickly disappeared. It did well overseas, and in 1992 was briefly rereleased to art and revival houses in the US where more- appreciative reappraisals still failed to result in a significantly higher profile. Well-regarded and ranked by both of its lead actors as their career favorite film, The Honeymoon Killers never achieved the kind of mainstream recognition its widespread critical acclaim augured, but over the years it has built a steady and devoted cult following, becoming a marquee mainstay at revival theaters and midnight screenings. Today, it’s hailed as a modern classic of gritty realism by first-time director/screenwriter Leonard Kastle, a one-hit wonder who never made another film.

|

| Shirley Stoler as Martha Beck |

|

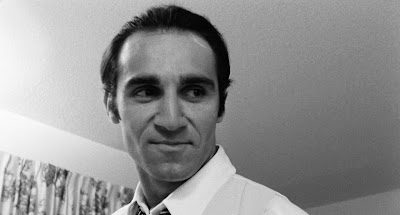

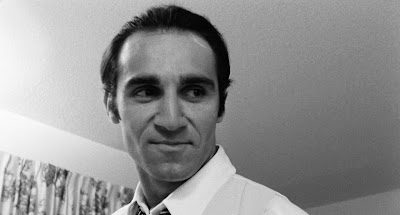

| Tony Lo Bianco as Raymond Fernandez |

.JPG) |

| Doris Roberts as Bunny |

The Honeymoon Killers is based on one of those stranger-than-fiction true crime cases so bizarre that it has to be toned down just to register as even remotely credible on the screen. An unlikely pair—surly nurse Martha Beck and unctuous con-man Raymond Fernandez—meet through a Lonely Hearts Club, fall in love, and embark on a larcenous, ultimately murderous, partnership swindling lonely widows out of their savings…and doing away with the ones who give them trouble.

The real-life duo, dubbed the Lonely Hearts Murderers by the press for their practice of finding their victims through meet-by-correspondence Friendship Societies and Lonely Hearts Clubs, embarked on what one journalist referred to as their “Career of lust and murder for profit” in 1947. They were finally arrested for their crimes in 1949, and both executed in 1951.

|

| To be together as Ray carried out his seduce-and-abandon schemes, the pair posed as brother and sister. In real life, Martha more credibly pretended to be Ray's widowed sister-in-law |

The Honeymoon Killers is bookended by documenting title cards asserting its factual basis. Opening with a printed declaration of the truth of the events to follow, the film closes with a verifying coda citing March 8, 1951, as the date of Martha and Ray’s execution by electric chair in Sing Sing prison. Given all this, what fascinates me is that while the narrative details of the movie hew closely to the facts, absolutely nothing about the film’s appearance…from automobiles to clothing to hairstyles to décor…ever gives the impression of taking place during the years 1947 to 1951. The look is completely late-1960s. In fact, one scene has Martha using a Princess Telephone (invented 9 years after her execution), and another places her in the kitchen with a 1968 wall calendar in view. What fascinates me about all this is that it matters not a whit.

Martha's mother (played by actress Dortha Duckworth) plays DJ for visiting guest, Ray, the handsome "Latin from Manhattan" who traveled all the way to Alabama to meet (and wheedle money out of) Martha, his most recent Lonely Hearts pen-pal. The LPs lined up for the occasion are several era-specific favorites: The 1958 debut album by The Kingston Trio: Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass' ubiquitous 1965 album Whipped Cream & Other Delights, and epic novelist James A. Michener shares his Favorite Music of the South Sea Islands from 1965.

Who needs period detail when you have Oliver Wood’s exquisitely grimy, documentary-style B&W cinematography turning every frame into a gritty crime-scene snapshot straight out of a ‘60s issue of True Detective Magazine? I have a hunch that what was perhaps simply a consequence of the film’s prohibitively small budget wound up serendipitously granting The Honeymoon Killers the aura of an intentionally revisionist updating of the traditional ‘40s crime noir. Particularly the nihilistic, gritty, crime noirs like Detour (1945).

If it’s true (as historian Ryan Reft suggests in his 2017 essay When Film Noir Reflected an Uneasy America) that ‘40s film noir “…depicted a nation in which the American Dream was treated as a ‘bitter irony,’”; then it's therein that I find in The Honeymoon Killers' '60s look and cynical perspective, a seamless affinity. With its vivid merging of the stark, grainy look of documentary with the impressionistic lighting and stylized framing of film noir, the mood and atmosphere of The Honeymoon Killers resonate with me as reflective of American moral and spiritual ennui during the Vietnam era.

|

| Hungry for Love |

Although seen early in the film responding angrily to her mother referring to her as "My little girl," Martha is nonetheless frequently depicted in ways emphasizing her childishness. In scenes shared with Ray and his temporary wives, Martha behaves pretty much like an ill-tempered 200-lb toddler left in their charge. When not complaining, throwing a tantrum, or sulking petulantly, Martha's childlike inability to control her impulses extends to her sexual rapaciousness, her appetite for candy, and her homicidal possessiveness of Ray. A delusionally blinkered devotion fostered by the idealized depiction of adult relationships in her ever-present Romance magazines.

The Honeymoon Killers’ unpleasant characters, blunt violence, and air of austere ugliness is the purposeful attempt on the part of producer Warren Steibel and director-screenwriter Leonard Kastle to rebuke and repudiate the embroidered approach of “based on real events” crime movies like

In Cold Blood (1967),

Bonnie & Clyde (1967), and

Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969):

“I wanted to do (this film)…in a form that didn’t sentimentalize or romanticize murder. I’ve always thought that the way people like this are represented, in Hollywood especially, is terrible. They are either made too evil, so that they are no longer human, or they are made too sweet, or, sometimes even beautiful.” Leonard Kastle - The News and Observer June 4, 1970

The Honeymoon Killers has much to recommend it and is one of those films that feels like it's far more violent than it actually is because of its bleak tone and pervasive air of dread. With each new Lonely Hearts encounter, I found my jaw clenching tighter and tighter. The assured performances of Shirley Stoler and Tony Lo Bianco are compellingly raw in their total disinterest in coming across as sympathetic or likable. I can't say enough good things about the intensely evocative cinematography, and I love the ingenious use of the music of Gustav Mahler on the soundtrack (goosebump-inducing!).

But had true crime exposé and sensationalism been the only things on the film’s mind, I’m not sure the movie would have held much appeal for me beyond morbid curiosity. But The Honeymoon Killers is anything but your typical crime film (a police presence is nowhere to be seen). A minor masterpiece of the macabre, it’s a contextually rich and narratively provocative film whose dire themes offer a trunkload of things to unpack.

WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THIS FILM

In approaching a film like The Honeymoon Killers, I can’t say that I expected to see anything of myself reflected in the grubby saga of these notorious callous murderers. But I did hope that in its characterizations, I’d find traces of something, if not necessarily sympathetic, then perhaps recognizably human. Kastle's perceptive screenplay and the realized performances of the outstanding cast meet this daunting task with admirable sensitivity and an unexpected degree of psychological and social insight.

Indeed, one of the more unanticipated twists of The Honeymoon Killers is that in its depiction of the nature and design of the duo’s criminality, a shadow portrait of contemporary American culture is painted, allowing the unsavory case of The Lonely Hearts Killers to assert itself as a uniquely American kind of nightmare.

|

The CEO

Ray refers to his practice of swindling gullible and lonely

old ladies out of their savings as his "business."

|

Martha Beck and Raymond Fernandez, like the grotesques in Nathanael West’s

The Day of The Locust, are embittered fantasists whose misdirected discontent with their lives fosters contempt for conventional society. An amoral resentment that fuels the compulsion to strike out at a world they perceive as having somehow shortchanged them.

Ray, in his picayune ambition and greed, is the American “success ethic” writ small. His so-called business being the heteronormatively “unmanly” occupation of trading on his looks and sexual desirability, Ray buttresses his masculine insecurity (linked also to his hatred of women) by adopting an absurd machismo: (To Martha’s suggestion of returning to nursing to pay their bills) “…no woman’s going to support me!” Of course, that’s all women have ever done for him…granted, either unwittingly or posthumously.

|

| Nurse Wretched |

For her part, Martha clings to the romantic banalities of the distaff side of the American Dream that profess a woman’s greatest happiness is found in marriage and family. But with no maternal instincts to speak of (we see her kicking a child’s wagon out of her way as she walks home) and only her emotionally manipulative mother for company, love’s lack has turned Martha into a clenched fist of bitterness.

The obvious intimation that Martha’s obesity is the cause of her desperate loneliness is quashed about five minutes into the film when it’s confirmed that Martha’s biggest hurdle to intimacy is her astoundingly lousy personality. Surly, sullen, sneaky, and hostile (and let's not forget anti-Semitic), it’s a perverse irony that her only remotely humanizing traits—her love for Ray and the wish that they might be married and move into a house in the suburbs—are responsible for the unleashing of her darkest, most inhumane self.

Spreading my The Day of the Locust analogy even thinner, in West’s novel, LA’s disillusioned are depicted as wholly ineffectual as individuals, yet a destructively violent mob when joined with the embittered like-minded. Separately, Martha Beck and Ray Fernandez were but miserable sociopaths living out their drab lives.

But when they met (to paraphrase Max's famous intro to TV's Hart to Hart)...

|

| ...it was murder. |

THE STUFF OF DREAMS NIGHTMARES

The most fitting term I’ve heard coined to describe the look and feel of The Honeymoon Killers is American Gothic. Indeed, its low camera angles and deep shadows call to mind gothic horror as readily as film noir. But also, in Ray and Martha’s cynical exploitation of lonely women whose unfiltered, often foolish, belief in the “Happily Ever After” ideals of romantic myth leave them vulnerable to opportunists; The Honeymoon Killers offers mordant commentary on the foundational myths of American culture (marriage, morality, religion, patriotism). A harsh indictment and social critique consistent with late-‘60s zeitgeist cinema expressing disillusionment with the American Dream.

Nobody’s dreams are realized in The Honeymoon Killers.

.jpg) |

| Ann Harris as Doris Acker |

The blushing bride is a New Jersey schoolteacher for whom Ray's disdain is displayed early on when he accidentally-on-purpose refers to her as a spinster. And most certainly later when he consummates the marriage with his "sister" instead of his wife. Robbed of $2000 and some jewelry, Doris escapes sadder but wiser, the biggest crime committed during that honeymoon being the atonal rendition of “America the Beautiful” she sings in the tub.

|

| Marilyn Chris as Myrtle Young |

As cons go, Ray’s 2nd marriage is kinda on the up and up. To keep up appearances and stay in good with her wealthy family, Myrtle pays Ray $4000 to marry her so she can have a husband’s name on the birth certificate when she delivers her illegitimate child fathered by “…a certain married sonofabitch” back in Arkansas. Things only begin to go south for the Southern belle when she starts to show some “not in the contract” sexual interest in Ray.

|

| Barbara Cason as Evelyn Long |

A merciful misfire. A mix-up match-up brought about by Ray mistaking Evelyn's boarding house for a mansion, the union is doomed from the start due to the atypically youngish woman being intelligent, gentle-natured, and athletic. In short, everything Martha is not. In an ironic twist, Martha’s jealousy actually ends up saving Evelyn from harm and heist.

|

| Mary Jane Higby as Janet Fay |

The absolute jewel in the crown sequence of The Honeymoon Killers. Higby as Janet Fay--a pious, penny-pinching, amateur hat-maker with one of the most spot-on hilarious speech patterns--would walk away with this virtuoso vignette had not Stoler and Lo Bianco brought out the big guns and so seriously killed it (bad, ill-timed pun) with the drop-dead (sorry, folks) chilling intensity of their performances in this sequence. Walking a delicate tightrope between black comedy and darkly disturbing horror, the film turns a corner with this segment, and Mary Jane Higby gives one of my all-time favorite supporting role performances.

|

| Kip McArdle & Mary Breen as Delphine Downing and daughter Rainelle |

Ray has plans to marry this pleasant military who irks Martha with her youth, avid patriotism (she throws birthday parties for ex-Presidents), and penchant for serving health foods. Things go wrong in a hurry and in a big way when Martha learns that her sweetheart...remember him, the professional liar?...has been (surprise!) lying to her.

|

| "You promised!" |

“I always made sure I wasn’t a sight gag. I used my weight as an ominous instrument” - Shirley Stoler in a 1998 interview (she died in 1999) for

Index Magazine.

Shirley Stoler (who would later appear in Lina Wertmüller's Seven Beauties and--most memorably for me---as Mrs. Steve in the first season of Pee Wee's Playhouse) is flawless as Martha Beck. When The Honeymoon Killers was made, a woman of plus-size was a familiar staple of comedy, but extremely rare in a dramatic context or as a character meant to be regarded seriously. Typical of both the era and the genre, when it came to marketing the film, Martha Beck's weight was a central focus of exploitation. Posters for The Honeymoon Killers sought to shock with images of Stoler posed assertively or erotically (caressed and kissed by a shirtless Lo Bianco) in her underwear.

In the film itself, Martha's weight is treated with far less sensationalism. In fact, the movie is cannily content to let viewers implicate themselves as to whether or not they find the romantic and sexually-charged pairing of these two reprehensible murderers more distasteful because of who they are or because of the disparity of their appearance.

.JPG) |

| Bad Romance |

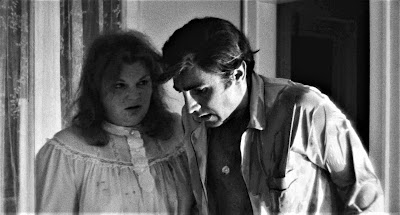

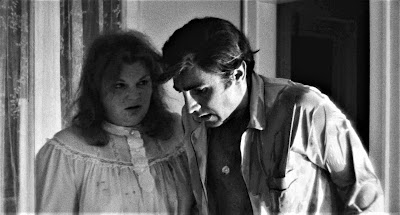

Shirley Stoler's performance is so dynamic that Tony Lo Bianco's seductively sinister portrait of evil is often overlooked. Playing a manipulative sociopath who dons many masks (and a toupée) to get what he wants; Lo Bianco is assigned the difficult, hall of mirrors task of imbuing a shoddy, superficial loser with layers of depth that are both inaccessible and unrecognized to him, yet must be conveyed to the audience. Lo Bianco has two remarkable scenes (both involving heinous acts of violence) in which Ray's cracked facade reveals the weak, dependent man underneath. The pitiful beast behind the beauty.

.JPG) |

| A nightmare of psychosexual dysfunction |

Cinema's conventional gender inequity of exposing the female form while keeping the male body clothed is reversed in The Honeymoon Killers. The camera trains a scopophilic eye on Ray, centralizing his body in various states of exposure and undress. Ray's body is presented to us in a manner not dissimilar to the way Ray uses his body in his profession...for purposeful display and deliberate enticement.

THE STUFF OF LEGACY

One factoid about The Honeymoon Killers that doesn’t get much traction (if any) is that it is a work of Queer Cinema. Not for content (although I suppose one could mount a critical theory around latency being behind Ray's narcissism, sexual self-objectification, and manifest hatred of women), but because the film is the collaborative creation of two gay men.

|

Sex Sells

To better secure a distribution deal, small-budget independent filmmakers are encouraged to make sure their movies have enough "sex." This usually translates to frequently exposing the female form to the hetero male gaze. The Honeymoon Killers provocatively breaks with tradition in having Ray be the film's "sex" object, with the camera often adopting the hetero-female and/or queer male gaze.

|

Director/screenwriter Leonard Kastle (an opera composer and music professor at the State University of New York in Albany) and producer of The Honeymoon Killers Warren Steibel (Emmy Award-winning TV producer) were a couple who shared a life for 25 years in their home in New Lebanon, NY. Their personal and professional relationship dissolved in 1980, several years after which Kastle sued Steibel for business fraud, a claim Steibel sought to have dismissed by the courts on the grounds that he believed the lawsuit was merely a bid for palimony.

That Kastle & Steibel had to be closeted or discreet during their years together is understandable, as they must have met in the 1950s and Steibel produced the conservative TV news commentary program Firing Line hosted by William F. Buckley Jr. But since their deaths (Steibel in 2002, 2011 for Kastle) it's dismaying to read contemporary bios and articles referring to these two single, childless, middle-aged men as having been "roommates" for 25 years.

|

| Leonard Kastle |

Much is made of and considerable mystery surrounds the fact that Leonard Kastle, whose debut feature film was hailed by the likes of Truffaut and Antonioni, never made another movie. Shirley Stoler in the aforementioned Index Magazine interview and Tony Lo Bianco in a

2021 YouTube interview for the Albany Film Festival offer at least one possible answer. Both state that Kastle--who was never slated to direct the film to begin with--had

"no experience" and was

“no director,” and that the person who really did the lion's share of the directing and shaping of

The Honeymoon Killers was the same man responsible for its distinctive and celebrated look...British cinematographer Oliver Wood (

The Bourne Ultimatum,

Fantastic Four,

Safe House).

|

Looking at the magnificent composition in this low-angle shot: oppressive ceiling, packing boxes, Martha's soon-to-be-abandoned mother sitting despondently in the far distance with her exit doorway not far behind, the tacky TV trays, the dowdy housedresses whose similarity underscores Martha and Bunny's conspiratorial closeness...it's hard to doubt or second guess Oliver Wood's influence and impact on the production.

|

Assisting Wood with the directing chores was Tony Lo Bianco, at the time an experienced theatrical director and the creator of NY’s The Triangle Theater. He helped the first-time screenwriter Leonard whittle down the script before the film’s original director, young Martin Scorsese, took the helm. Scorsese was fired after two weeks for working too slowly (Lo Bianco cites the scenes at the lake and the railroad station as Scorsese’s work). Both stars relate that directing duties then fell briefly to a second individual, an unnamed ex-film editor described by Stoler as “...a kind of quasi-derelict.” Oliver Wood then took over directing the film in an unofficial capacity and, according to Lo Bianco, Kastle only came onto the film as director during its final days, directing the film for “A week and a half or two weeks, tops" yet claiming sole onscreen credit as director.

BONUS MATERIAL

|

| The fictional and real Ray Fernandez and Martha Beck |

|

The Honeymooners

The late actor Guy Sorel (who portrays Mr. Dranoff, the hospital administrator who fires Martha for the obscene letters he finds in her desk) and popular radio actress Mary Jane Higby (who plays the ill-fated Janet Fay) were a couple in real life. Married in 1945. Isn't that cute?

|

|

| Regina Orozco and Daniel Giminez Cacho in Deep Crimson (1996) |

The Beck/Fernandez "Lonely Hearts Killers" case has served as the inspiration for at least three other films that I know of. To date, the only one I've seen is the superb Deep Crimson (Profundo Carmesí) -1996 by Mexican director Arturo Ripstein. In 2006 Todd Robinson directed Jared Leto and Selma Hayek(!) in a more police investigation-centric retelling of the story titled Lonely Hearts. And Alleluia (2015) is a French/Belgian adaptation directed by Fabrice Du Welz that updates the story to a contemporary setting.

Copyright © Ken Anderson 2009 - 2022

.JPG)

.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)